"Zielnik Pilski" by Boguslaw Biegowski, or what is photography about?

The biggest difference is that technology and the internet has speeded everything up tremendously in just a few years. We take the instant transmission of photos and text for granted. As a photojournalist for 60 years, I well recall a different time when I would send packages of undeveloped rolls of film with hand written captions to editors all across the world. DHL and FedEx were vital for my international work, even the regular mail system on occasion. Then digital cameras and the internet came along, changing everything, and a lot more time had to be spent at the computer. Newspapers were the first to take advantage of the technology as they require a quick turnaround for news stories and photo quality was less demanding. It took longer for color magazines to adapt, the sort I worked with, who had to wait until digital photography improved. Online media didn't exist at all until relatively recently but it certainly didn't kill print media, as some predicted. With a certain shyness I took out of the drawer my text from years ago, which, I think, has not grown old, because the Boguslaw Biegowski exhibition analyzed in it, one of the most important in his oeuvre, has never been shown in large, professional galleries, except for the episode in W wągrowiec, which I refer to in my text - This is how Krzysztof Szymoniak's letter began, which reached the editorial office on December 31, 2022.

The text is extremely long - almost 60,000 characters with spaces - and on top of that it is richly illustrated, so its "consumption" is not quick. It is addressed not to everyone, but to people who not only like to read in-depth analysis, but also enjoy the effort of their own interpretation of photographic work. At the end of the text, the reader will find a bonus in the form of deciphered all the comments handwritten by Biegowski on the passe-partout under the photographs (editors).

1.

On the night of February 9-10, 2012, it is minus 14 degrees C outside the window of my house/apartment. This small house (actually a small house) stands in the eastern suburb of Gniezno. In a week's time (eight days to be exact), from Friday to Saturday, I am to spend a similar frosty night in Wągrowiec. Last night (February 9) I talked about photography with Boguslaw Biegowski in Poznan. I am also scheduled to talk about photography with him on February 17 in the evening in Wągrowiec. Our conversations about photography and photography sometimes start with questions and end with a question. On the night of February 9-10, I had a dream. I dreamt that I was reading a letter from Boguslaw Biegowski to fellow photographers, which began with the words: I can't take you with me. In this dream, the house was full of people (men and women) of an age conducive to socializing. Boguslaw Biegowski distributed this letter (a printed piece of paper) to all the people present in the dream. These people, that is, the photographers who entered the dream, asked questions, wanted to know more, wanted to understand, but the author of the letter referred them to the source, that is, to the letter. Everything is there," he said, "what you want to know, and what I wanted to convey to you.

I, writing these words, dreaming that dream, did not recognize the contents of the letter. I only remember this first sentence: I can't take you with me. So I don't know what the author of this letter wanted to convey to his fellow photographers above, and I don't know what they wanted to learn from the letter's author. I can only guess at both of these things, but in this case, too, I can't be sure that my curiosity isn't leading me astray. The first and basically the only clue that could in any way illuminate somewhat the mystery of my dream has to do with something that happened two years ago, specifically on February 5 and 6, 2010. That was when I met Boguslaw Biegowski. We met in Licheń, where he was to lead a photography workshop for adult amateurs, organized by Konin's Center for Culture and Art (in the persons of Beata Mazurek and Pawel Hayman) and WBPiCAK, while I was preparing for another talk in the series of Photographers of Greater Poland. Recall that this series was coordinated from the beginning by Wladyslaw Nielipinski, and began to be published in 2009 under the vignette of the Provincial Public Library and Center for Cultural Animation in Poznan. I went to Lichen to get to know Boguslaw Biegowski unhurriedly, far from intellectual shallows, journalistic news and information noise, to see how he works and to find out what he thinks about photography and photography. The conversation with him was to somehow determine the fate of the entire series and my presence in this endeavor, calculated over several years.

The most significant of that meeting - for present considerations - was the second day of the workshop, when the organizers invited all workshop participants to an open-air photographic session at the Lichen Basilica, which was open to the faithful, but deserted in the middle of winter (and during the crackling cold). There were a total of a dozen of us there (maybe as many as twenty, with the organizers) and a local guide who provided the future masters of the lens with access to all the attractive (from a photographic point of view) rooms, levels and nooks and crannies of this huge temple - from the ground floor, through the interior balcony, to the observation tower. I remember that Boguslaw Biegowski suddenly broke away from the group after viewing the ground floor rooms and - without explaining himself to anyone - disappeared from the eyes of the rest of the company. On that day, February 6, when all the workshop participants, without exception, were saving dozens, or rather hundreds of frames/files on the memory cards of their digital cameras for two hours (because, after all, it doesn't cost anything), he, in total silence and solitude, set up his 9 x 12 cm travel box camera to photograph just one place, one motif. It was a room filled with a dozen or so large agaves in wooden pots, which most simply overwintered there. This photograph later entered our conversation, as a black-and-white image that closes the book. It depicts a thicket of thorny arms-leaves (filling the entire frame) against the background of a small section of wall and an even smaller section of light-shedding window. If one were to read this image directly, interpreting it 1 to 1 according to what is seen in it, there is nothing of the architectural enormity and aesthetic uniqueness of the Lichen Basilica. If it were not for the caption under the photo directing the viewer, almost certainly none of those who have never seen a room filled with huge cacti in Licheń would be able to assign this photograph to the collection of already existing photographic images of the temple, describing and showing it in many possible, indeed different, ways. The author of this photo later said that since he had run out of the right tool during his stay in Licheń (quote: I would have liked to have had a large digital camera at the time and rendered every lump of gold with it), with which he could photograph the Byzantine splendor that is omnipresent there, he focused exclusively on these dozen agaves as a symbol and at the same time the quintessence of Lichen's splendor, excess, density. Does this story explain anything and have any relation to the phrase: I can't take you with me? This is just a clue, but - I think - quite expressive.

2.

Ok. Before you start watching and researching Pilski herbarium Boguslaw Biegowski, first try to watch and study four, by the way, the first from the shore, black and white films: Eight and a half Frederic Fellini, Matnia Roman Polanski, Last day of summer Tadeusz Konwicki, State of affairs Wim Wenders. What do they have in common from the point of view of our considerations? Only that they are very photographic. In any case, I do not intend to add any additional story or even history to this cinematic four-pack. I am not an ideologue or an advertising salesman. So a quote from a Wim Wenders film is enough for me: Well - life is in color, but black and white is more realistic. Nor do I claim that these films have anything to do with the Pilskie Zielnik, I just want to point out to the reading public a certain non-trivial psychological feature in terms of perceiving the world (as it is), a certain way of thinking with photography, valuable, interesting and important in Biegowski's oeuvre, and regardless of everything, materializing, among other things, also in the work of several talented directors cited here. It is they, the artists of cinema, especially the non-commercial ones, who come to the conclusion over time that black and white cinema is about life as it really is. And since that's the case, people - thirsty for colorful plots about non-life - don't want to watch it. Now let's ask, do people, especially residents of big cities and medium-sized cities scattered around the country, unreflectively immersed in a space controlled by color photographic images of often unknown origin, want to watch black and white photography today? Especially to watch consciously? And one more thing: if black and white cinema is about life as it really is, what is non-commercial black and white photography about? Especially analog? Once we've dealt (dealt) with these two questions, let's look (look) into the world of Boguslaw Biegowski's photography and ponder (ponder) for a moment what his black-and-white analog non-commercial photography is about Pilski herbarium?

An exhibition of photographic works with this title appeared for the first time on July 2, 2011 in Wągrowiec, in the gallery of the Municipal Cultural Center. The exhibition, which consisted of 9 x 12 cm styrofoils and several 4 x 5 inch styrofoils, was accompanied by a modest folder, fortunately provided with an interesting text. It came from the hand of the author of the photos. Photographers usually don't write such texts, they even shy away from this type of work, but what B. Biegowski is able to write about himself (his photographic activities) is an introduction and reflection of high quality. Anyway, what's there to divagate, let the word speak:

Genesis of the project. The immediate impetus for the topic was an author's photo card I recently received from Rafal Nadolny, a day care resident in the capital city. The photograph shows a multiplied, expressive image of an airplane-monument in Skierniewice. Title of the work: There was a province. I realized that My Province also no longer exist. Photographs taken over the years without any specific purpose or goal began to slowly arrange themselves into pairs, longer sequences and sequences. Thus was born the idea of a collection, a collection of photographs depicting something that no longer exists. Something past, dead and dried up, yellowed and systematized and frighteningly devoid of expression. Herbarium with equal meticulousness collects both images of endemic specimens, such as the monstrous concrete swords guarding the entrance to the interior of the territory, but also typical railroad water towers. Creating the document is a pioneering expedition into the depths of his own archive, but also ongoing fieldwork. Reaching the "transparent", invisible artifacts, previously unconscious. All the works presented in the exhibition were created in the 21st century, already after the liquidation of the Province. Exhibited for the first time in Wągrowiec, the contact copies are the only, author's copies of the photographs. The formal diversity of the works on display is a testament to the doubts and searches and the belief in the magical power of the photographic original. The collection has no ambition to be a Pila monograph. For example, omitted (with the exception of one photograph in the exhibition) is Trzcianka, which has a separate, not yet presented, collection of photographs titled "The Pilsen. T.R. Schonlanke.

The other two parts of this text, viz. Pilsenism. The origin of the myth and My Province and in it..., are an important part of the introduction to the world presented Pilski Zielnik, which by itself does not explain everything the author considers important. Important, for example, from the point of view of the perception of photographic images (those here, concrete), but also at the level of the viewer's understanding of the historical references and cultural references (in accordance with the semiotic theory of the sign, which assumes that the sign refers to something) that the entire exhibition carries. For there are many indications that an important rhetorical message from the borderline of aesthetics, intellect and emotion has been inscribed in these images, which is not insignificant for the sender and viewer. This observation is not just a customary essayist's quibble, as this "realm of aesthetics, intellect and emotion" reveals itself (in my mind) every time I approach the Herbarium at a distance of eye contact with its components, i.e. photographs, or rather small contact copies. Thus, it can be assumed that the above-quoted excerpt from the text (about 1/3 of the total) effectively introduces us to the essence of the issue, but the fact is also that in isolation from the exhibition it fails to convey one important piece of information. Namely, that each photograph, after being framed in a bright passe-partout and later included in the collection/exhibition shown for the first time in Wągrowiec, was enriched/enhanced with handwritten notes, reflections, notes and hints placed by the Author under each black and white frame. And this, in my humble opinion, is what makes this exhibition not only "watchable", it is also "readable" (both in the narrow and broad sense of the word). And while reading and watching (or watching and reading), the viewer ventures not only into the depths of the photographic archive, for he also ventures into the personal past of the Author of the works, and finally ventures into the increasingly "transparent" history of a certain province, which, after all, once did not exist, and which does not exist again. And if this is so, then we are dealing in the case of the Herbarium not only with the depicted world (images), but also with the linguistic image of the world (manuscript captions under the images). Now let's try to see these "signatures" and read them frame by frame, mainly to understand the photographer's intentions. Finally, let's try to interpret their content (not only informational or descriptive) and establish a possible typology of these para-commentaries. After all, it could be that the photographer, enriching his contacts with ephemeral, previously unplanned text, created a certain typology despite his intention, although it is not decisive for the overall project. Perhaps, however, there was here (within the captions) a pre-planned and therefore deliberate informational and stylistic procedure. And if this was the case, if this is what happened, let's ask, for what purpose did the photographer's hand make these notations? For example, was it to non-invasively reinforce the rhetorical message and structure of the individual thematic threads and the exhibition as a closed whole (enclosed in the space of the former Pilsen province)? Or maybe typology is not present in this matter, maybe it is simply a kind of typologically unformatted travelogue (or even an intimate notebook), in which words are combined with images without any particular intention? If this turned out to be true, then Hilary Putnam's famous question could be posed after Jerzy Kmita: How do words connect to the world? In this case, it would be about how the words from the annotations under Biegowski's photos connect to the represented world of his photographic frames.

3.

Let's start with the necessary - in my opinion - statement that, in the case of the contacts that have entered the Pilski Zielnik, the term "black and white photography" does not capture the essence of things. Black and white in pure form on these undersized pieces of photographic paper simply does not exist, while various shades of gray - from very light, to very dark - certainly dominate. That - first of all. Secondly - this entire set of fifty photographs, which make up Biegowski's exhibition in W wągrowiec, appeared in this arrangement as a preview. Importantly, these are not pretty photographic images, of the postcard type, from the former Pilsen province. Of course, some of the objects photographed for this series and included in the Herbarium may also have appeared in the past on typical, pretty, color postcards (especially those "grunwald swords"), but what the author proposed Herbarium, is a kind of aesthetic manifesto, a conscious effort of the artist on the photographic matter, and not - as it might seem to the not fully oriented participants of the vernissage - the result of a lack of workshop skills. Thirdly - Boguslaw Biegowski moves with his box camera in the often deserted public space, on the outskirts of cities, towns and in the vicinity of small railroad stations, connected in various ways with the once provincial town of Pila, the then center of the local cosmos. Wherever the artist views this cosmos through the lens of his camera, and then fixes a slice of it on a leaf of film, a silent spectacle of transience and decay takes place, or a literary, in a way, reconnaissance into the past hooked on the photographed objects, inscribed in personal spaces of memory. Fourthly and finally, let's consider whether these images, shown to the public for the first time in Wągrowiec, are the quintessence of a documentarian's reflection? Especially since in the introduction quoted here Biegowski says: Creating a document is a pioneering expedition into the depths of one's own archive, but also ongoing field work. Or rather, are the paintings a kind of expedition for the golden fleece, an attempt to read the private mythology that memory builds into specific objects and the things happening around them?

I once asked (on February 9, 2010 to be exact) the author Herbarium about something that used to be called photographic self-awareness. I also asked about the timing of its appearance to him. In response I heard, among other things: It used to be mostly intuitive. But this has remained with me to this day, this conviction that photography is something wild and untamed. It is not just what is in the photo, it cannot be reduced to philosophy, for example. Photography is a little somewhere else, it is primarily form, materiality and substance. In those early days there was a curiosity, which is still with me today, about how it would come out in a photo. I'm not particularly convinced that I have a mission in photography, that I have to document something, because after all, everything will fall apart one day anyway. It's just a matter of extending the memory. This building will disintegrate in, say, 50 years, and my photograph of it will cease to exist in, say, 150 years, but that doesn't change anything, because disintegration is inevitable. So my first motivations boiled down to running around with my camera and photographing everything - people, animals, places. I traveled around Poland, to some rock festivals, to some strange places and photographed there. It had no purpose, no methodology and probably no deeper thought, although when I look at those old photos of mine today with a certain fondness, I come to the conclusion that an artist doesn't have to realize all those things that a viewer, and especially a critic, who looks and says it's so fresh or revealing, realizes. Here is such a case, for example, Jacques-Henri Lartique. He took his famous photos in his teens at the auto races, photos that have gone down in the history of world photography. So immediately the question arises, did he realize that he was photographing cultural change, civilization, progress? No. He didn't realize it. And that's why I find it fascinating in photography, that there is an element there, so to speak, outside of culture. It is just so wild and untamed. (...) I often argue with my colleagues from the Common RoomThat awareness is not that important. Let's not overestimate it. Half of the valuable works of European culture, especially of the 20th century, were created outside of consciousness - Van Gogh, Witkacy, Bruno Schulz. This is the European tradition that valued the unconscious. This can be combined with the discoveries of Freud and Jung to remember that this is an important part of our personality, and even more broadly of culture. Jung even coined the term "collective unconscious." Also for me this is extremely important. I don't reflect all the time walking around with my camera that I will make some important record. I photograph for pleasure. I'm not a heroic photographer, and that's why I don't attach any special importance to the fact that here I am now making some kind of document that will remain for someone. All this is not so important, although I had a period in my life when I was close to this document. But it didn't come from the need to document, but maybe more from social needs, from the fact that historic architecture is deteriorating, that (...) space is something common and it's worth taking care of, not just selling it off and building closed enclaves in it. The document itself for me is not the most important thing, for me it's more about expression, it's more about my feelings when I photograph. Then the viewer, looking at my photos, gains symbolic power over them, he looks at them, evaluates them, but no longer has any influence on what is seen in the photos.

Well, that's right, the viewer has no influence on what is seen in the photos. But what is seen in the pictures, the viewer can subject to interpretation and, in extreme cases, over-interpretation. The case spotted and described by Umberto Eco is at work here open work - open to various interpretive possibilities. So, let's remind: we are now talking about just the photos in the collection Pilski herbarium, viewed just in case from such a distance that it is virtually impossible to read the manuscript annotations beneath them. What, then, can be seen on them from this very distance, when we take into account just looking, watching? The world as such, caught in the act of existence, existing independently of the will, perceptiveness and documentary activities of the photographer? Or rather, a disturbing pictorial tale of a world (in this case, a province) that no longer exists, even though some of its monumental or ruined remnants still hover in the vast landscape? At this point, the question posed earlier returns: What is photography about?. So what is it about? About passing, about lingering in a state of negative-positive hibernation, or about remembering what has just passed away and will never return? The waterworks water tower from Walcz, Saw, Wronki or Zlotow, which has just been photographed, will most likely survive the next wind gusts, rains and snowstorms, but nothing will reverse the stream of seconds, hours and days that have passed since the shutter button was pressed.

I wonder how it is possible (and if it is possible at all) to define/define the presented world Pilski Zielnik? In order to unravel this question, let us use the term introduced by Roman Ingarden presented world. W Dictionary of Literary Terms it reads:

The world depicted - one of the main components of the work, the totality of the phenomena presented in it (...) which are the object correlates of the semantic layer of the statement (...). The building block of the presented world is the thematic material exploited by the author, which is subject to selection procedures, interpretation and construction in accordance with a specific artistic idea, theoretical concept and ideological intention. The elementary units of the depicted world are motifs (...). The central component of the depicted world, ensuring its internal coherence and determining its overall arrangement, is the theme (...). Sometimes the depicted world is an elaborate sign indicating content not directly communicated in the work.

Leaving aside the minor fact that the term presented world was created with a literary work in mind - which, in my opinion, doesn't quarrel too much with trying to describe the Herbarium - then already the content of the above quote undoubtedly opens up an interesting (befitting photography) field of analysis, which in other circumstances (e.g., in the case of a conversation with the author after the opening) could be passed/recognized almost intuitively. So, what is it, in the case of Herbarium The biggest difference is that technology and the internet has speeded everything up tremendously in just a few years. We take the instant transmission of photos and text for granted. As a photojournalist for 60 years, I well recall a different time when I would send packages of undeveloped rolls of film with hand written captions to editors all across the world. DHL and FedEx were vital for my international work, even the regular mail system on occasion. Then digital cameras and the internet came along, changing everything, and a lot more time had to be spent at the computer. Newspapers were the first to take advantage of the technology as they require a quick turnaround for news stories and photo quality was less demanding. It took longer for color magazines to adapt, the sort I worked with, who had to wait until digital photography improved. Online media didn't exist at all until relatively recently but it certainly didn't kill print media, as some predicted. one of the main components of the work, the totality of the phenomena presented in it? Most likely, it's about what you see when you look, moving from frame to frame. And what can be seen? Water towers (usually railroads), station buildings and structures, licentious tenements or other equally flimsy residential buildings, public buildings (functioning or ruined), monuments, bridges, mausoleums, murals, monuments of industrial construction, haystacks or bales of straw packed in white covers, places of worship and places of summer recreation. This can be seen when one looks. The onlooker has the right at this point to wonder why he is seeing and viewing this particular set of objects. If he picks up the folder prepared for the opening and reads the text in it, he will know why the world depicted Pilski Zielnik is filled with a collection of photographs showing these, and not others, products of human hands. However, if the vernissage viewer does not read the indicated text and ask the author about the collection of objects presented in his work, he will be faced with the necessity of "experiencing" this exhibition on his own (mainly in an aesthetic and perhaps also cognitive sense), or rejecting its contents as incomprehensible in the semantic layer of expression and repulsive in the gray and small formats of the prints. Let's go further. If, as the quoted definition implies. The elementary units of the depicted world are motifs, it is their list in the case of Herbarium will not be difficult to determine. For here are: vertical motifs (e.g., water towers), post-industrial motifs (e.g., railroad objects in the process of taking place, their slow annihilation), road and movement motifs (e.g. railroad stations, bridge over the river and automobile transportation stops), urban motifs (buildings), rural motifs (staging facilities, murals, lakes), industrial motifs (distillery), ideological and cultural motifs (monuments, mausoleums, places of worship), and existential motifs (people and their habitats). Looking at Herbarium purely for a collection of photographs-motifs that document something, without delving into the captions under the photos, one does not perceive in the first instinct of perception the personal attitude of the author of the works to the photographed reality. Therefore, after viewing this exhibition, a question arises about its theme, which, as the definition implies. is the central component of the depicted world, ensuring its internal coherence and determining its overall arrangemente. So? Contrary to appearances, there is no easy answer here, because the subject of the Herbarium are not only the objects and spaces photographed by Biegowski. The subject is the way the former province no longer exists. The subject is the state of the matter filling this former province. Finally, the subject is the photographer's incessant journey through his small homeland, the land of his childhood and youth, moving unhurriedly with a bulky box camera and trying to understand (name, make sense of) his own returns to that land. What I like most from the definition by Roman Ingarden quoted in the excerpt is the last sentence: sometimes the depicted world is an elaborate sign pointing to content not directly communicated in the work. In this phrase is revealed, I think, the crux of the matter. In my opinion, at least, the whole of this Hagrowieck exhibition is an elaborate sign, and a sign, as is well known, refers to something. To what, then, does it refer Pilski herbarium? First and foremost to the question What is photography about?but immediately afterwards also to the statement that you will never understand it until you turn off the TV, until you leave your cozy apartment, until you stand behind the camera in any (though not always arbitrarily chosen) part of the cosmos and press the shutter button. It is not without reason that American masters of reportage and documentary are in the habit of saying that they photograph to find out what the world really looks like.

4.

The exhibition was arranged in such a way that the viewer, after reading the text in the opening catalog, could (had a chance to) immediately relate to the idea of the title herbarium. Thus, the paintings were grouped thematically - water towers together, urban landscapes together, rural landscapes together, ruins together, and so on. The presentation opened with stylized images showing three concrete Grunwald swords, a symbol and hallmark of the former Pilsen province (photo 50, 45 and 44; see. Annex), usually set up along roads that led deep into the territory thus marked. Interestingly, these three images, because of what they show, can be associated with the three crosses set up two thousand years ago at Golgotha, especially since the first one (photo 50) was larger - in terms of format - than the other two. It is therefore an iconic (a well-known motif here), but also an iconographic reference to Christian mythology; a reference, I think, unintentional in the case of the author and probably risky, because somewhat anecdotal, in the case of viewers, in whom the automatism of association worked (if it worked). The exhibition closed with a frame showing a rather mysterious tombstone cross (photo 32; see. Annex), under which the author has placed a caption: June 14, 2011, Lekno. Recent photo. The first rain in many days fell. I was in Lekno for the first time in 25 years. Lech and I were standing near some strange tombstone that had the eye of providence placed in the intersection of the cross arms. I couldn't think of anything. I knew the photo would fail. Twenty-five years is a long time. I exposed two leaves. I haven't developed the second one yet. Maybe someday... The rain was falling harder and harder....

Boguslaw Biegowski, a large-format artist, accurately describes (or just notes) in his traveling notebook all the facts of photographic expression. Thanks to this, we know exactly where and when the individual frames were created, and sometimes we also learn about the circumstances of the creation of subsequent images and the author's reflections related to these situations. From such notes came the manuscript texts placed under the stencils Pilski Zielnik. Some were created right on the spot where they were photographed, and were only transferred from the notebook to the passe-partout, while others only took their final shape when the photos were framed.

As we have previously established Pilski herbarium It not only lends itself to being watched. It can also be read. And in two ways - linearly, from the first to the last photo of the exhibition, or chronologically, according to the dates from which all the author's para-comments begin. Moreover, it can be read on two levels - on the level of meanings and signs corresponding to the photographed reality (a simple, detailed reference to the designators), and on the level of metaphor and myth, when the meanings and signs expand their semantic scope to include contexts signaled by the artist, such as ideological and existential, or historical and cultural. I dare say that these contexts - as in any attempt to metaphorize (or mythologize) reality - are important not only for understanding (decoding) the overall idea of the Herbarium. They are also relevant for someone who tries to penetrate deeper into Biegowski's photographic work with his reflection. So, since we're talking about reading, it's time to take a look at the linguistic picture of the world. In our case, it comes down to a few simple questions arising in the mind of the writer of these words. For example, what are the manuscript annotations placed by the photographer underneath the photos about and what are they? How, through them, does the author (if indeed he does so) characterize/define himself and his residence in the not so distant past of the now former Pilsen province or his present residence outside it? Finally, how do the words (but also the phrases) of these additions connect, on the one hand, with the presented (photographed) world, whose reality, or materiality, can be verified, and, on the other hand, with the inner world, which is beyond any simple verification, consisting of memory, emotions, life experience and professed system of values? Perhaps the writer of these words errs, perhaps he chose the wrong questions, perhaps he lacks knowledge and research competence, but certainly this (probably imperfect) attempt to describe Biegowski's work came from his fascination with traditional photography and the need to understand an artistic phenomenon that functions in the so-called technical and aesthetic niche, so far completely outside the commercial sphere. Behind this motivation are purely cognitive intentions and total disinterest. I am aware, of course, that hell is paved with good intentions (e.g., the hell of intellectual losers and weak essayists), but since I take responsibility for every sentence of this text, I am counting on at least a little forbearance from true experts in the matter at hand.

So, let's start with the fundamental question - what do they inform about and what are the handwritten notes placed by the photographer under the photos? First of all, if we look at them with an archivist's eye, they are a form of documentary signature, a chronicle of photographic activities (time and place and the circumstances of the negative's creation), they are a collection of metrics allowing us to trace the artist's several-year wandering along the roads and off-roads of the former province, marked by not randomly selected stops. Meanwhile, in the non-chronicle layer of the text, these handwritten notes, placed under the included Herbarium framed, are a kind of fractious travel notes. They are reminiscent of Edward Stachura's concise and poetically infused notes from his recently published two volumes of Diaries titled Travel Notebooks 1 i Travel Notebooks 2. There is in them a simple statement and an existential reflection, a memory from youth and the leaven of a longer story, a metaphor and the reflection of an anthropologist. These notes not only inform about the time of work and the place of residence of the photographer-self-taught native of Trzcianka, they also approximate (name) the photographed reality and define the author's emotional states, against which naked photography is most often powerless. Or rather, incapable of self-explanation, of naming what-is-in-the-frame, of conveying to the viewer the knowledge of that what-is-outside-the-image. The language of photography in its referential function refers the viewer to real objects and phenomena, but under Boguslaw Biegowski's hand, well, and in the case of the very Herbarium, becomes a medium somewhat vulnerable to the image-sign, but also a medium insufficient to describe and accurately comment on what-is-seen. Hence, the conscious combination of image and text is not surprising. There are many indications that - even as an experimental attempt to communicate with the viewer - this combination is legitimate and purposeful. At least in my view. This procedure, sometimes to the sincere surprise of the cinematographer himself, offers the participants of the vernissage a new quality of the artistic event/act, creates an opportunity for a deeper insight into the photographic frame, and thus allows a widening of the sphere of perception, an action that not only interestingly, but also promisingly goes beyond the horizon of banal literary deeds.

Another point - let's ask, how, by means of these very promising literary events, does the author (if he actually does it) characterize/define himself and his sojourn in the not-so-distant past of the now former Pilsen Province or his present sojourn outside it? This minor caveat - "if he actually does". - stems from the fact that the writer of these words does not know (because he cannot know either, since he has not conducted a sociologizing interview with the author for this circumstance Herbarium), or B. Biegowski, when arranging his exhibition, completing the images that were to make it up, felt the need to characterize anything in connection with his long-standing residence within the former province. Assuming, however, that such a circumstance occurred within the textual layer of the Pilski Zielnik, perhaps in passing, let's try to pick up this thread out of mere curiosity. Contrary to appearances, the collection of short and utterly brief handwritten notes, which were found under fifty photographs, makes up a fairly substantial set in total (see -. Annex) notes, descriptions and comments. Their unquestionable cognitive value, but also - already mentioned - literary value, made the exhibition something like a story, not just a presentation. The considerable amount of self-talk that can be seen in these handwritten notes, regardless of the author's possible intentions (or lack thereof), allows the viewer (viewer/reader) to reconstruct at least a residual portrait of the photographer's man and gather a handful of his unorthodox views. It is this endearing lack of orthodoxy, this undisguised aversion to any fundamentalism that makes Biegowski (whether he wants it or not) a person sympathetic to the world, sympathetic to the local community, and endowed with a natural tendency to empathize with others. The author of these notes does not fall into cheap exaltation (when he refers to the mythology of the now former province), but neither does he look at that time and that land from the position of a merciless scoffer. All his attempts to look at what was and what is (at the time of photography) are full of warmth, understanding and even pietism shown to the surrounding reality. In the textual layer Herbarium It is difficult to find any aggression and resentment (emotional or verbal) towards the hardships of one's own growing up (not easy childhood, not very comfortable youth) and towards the past era and the political and economic realities of the time, while there is a lot of good energy, almost tenderness in dealing with - not only one's own - life and (jointly owned) inanimate matter. All this together evokes atmospheres from the land of gentleness, not only growing day by day into the sometimes brutal order of this world, but also - which is a value in itself - confessed with every written sentence as an ongoing act of faith. And one more thing - Biegowski's autothematic remarks, hidden in the notes and having to do with the art of photography he practiced, allow us to better understand his unfortunately still scattered views and important statements related to this fact, which refer to both the theory and practice of this very field of artistic expression.

What remains to be briefly considered is the final question - how do the words of these additions connect with the depicted (photographed) world, on the one hand, and with the author's inner world, which consists of memory, emotions, life experience and professed value system, on the other? Just by way of reference to sources, let us here mention Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose earlier A logical-philosophical treatisey and subsequent Philosophical inquiries sparked a 20th-century discussion, which continues to this day, about the understanding of the connecting words to the world. The different types of this understanding, which are already outlined - respectively - in the Treaty i Investigations, can, according to Jerzy Kmita, be given the names: semantic understanding and causal understanding. Without going further (due to the lack of competence of the writer of these words) into purely philosophical considerations, let's try to discern the issue in a few sentences Pilski Zielnik exclusively at the level of facts and words. Facts - are contact prints, which show "some" reality, past and present. It is the photographer's own (acquired by virtue of his place of birth and residence) reality, inscribed in the history of his life. It also constitutes the conventional (in the sense of a top-down administrative decision) framework of his former world, i.e. the Pilsen province. Words, on the other hand - recorded and attributed to specific facts-images that make up the Herbarium - are directed to the center of this world, although they were created outside of it. This, I believe, is the basis of this connectivity, free from artistic creation and journalistic manipulation, a connectivity that originates in the attempt to name what-was (the reality of the Pilsen province) and the search for identity within what-is (the living mythology of a place within the material remains of a dead structure). In a way, this situation resembles the condition of a lover of the ruins of ancient Greece, who views them, tames them (physically and mentally), who "experiences" their form and content, following the mythology of the ancient Greeks, but also being aware that this mythology has become permanently entwined with their real and partly reconstructed history. This is how I see it when I think about material reality Herbarium and the reality of the world to which Biegowski's photographic images refer (return). And the inner world of the artist? The emanation of what this world contains, how it functions and towards what (perhaps) it is heading, are the explicitly stated (sometimes also metaphorizing his own message) remarks and reflections spread over fifty handwritten notes placed under fifty large-format stencils. They can be examined and disassembled, and finally - following Jerzy Kmita - understood semantically or causally. But this is a proposal for another text and a completely different circumstance. Now that's all there is to it. Everything that the undersigned (or above) recognized in the Pilsen herbarium For important, valuable, interesting. And what he didn't deal with, let smarter people than him research.

ANNEKS

Photo 1 (IMG_4909) - March 17, 2006, Saw. Water Tower. Adopted as an apartment by Mr. Lewinsky. Sprucing up the holes and putting in plastic windows very debatable. Here I learned that there are about 800 water towers in Poland. Since then my enthusiasm for photographing them has waned considerably.

Photograph 2 (IMG_4910) - August 20, 2007, Piła Główna. Railroad infrastructure is perhaps the least susceptible to change. Its longevity is astonishing. Railroad towers were built right next to the track line. They are uninhabitable. They will stand until they fall apart.

Photograph 3 (IMG_4911) - March 17, 2007, Saw. The third tower, actually a reservoir. In my private typology I divide cities into those with a water tower and those without. Three towers is already something.

Photograph 4 (IMG_4913) - August 19, 2007, Pila near the PKS station. I came to Pila after more than a dozen years. The Stairway to Heaven, as we called it, was still standing, as it had been thirty years ago when I first photographed it. I experienced the political transformation in Poznan. Saw remained unchanged in my imagination.

Photo 5 (IMG_4915) - August 20, 2007, Saw, music school. Music for me has always been associated with grace and sublimity....

Photograph 6 (IMG_4916) - April 1, 2011, Wronki. I've been to Wronki about twice, maybe three times. I always felt some kind of pressure there. Last time I only understood where it was coming from. I imagine that in a moment there will be a prison riot and a mass of enraged villains will pour out from behind the walls, destroying everything along the way. I must have watched too many American movies.

Photograph 7 (IMG_4917) - March 17, 2006, Biała Pilska. Biala Pilska was arousing fear among travelers on the last train of the Krzyz - Pila relation getting off in Trzcianka. The darkest dream - to pass the station and wake up in Biala. On foot at night some 8 kilometers. Horror.

Photograph 8 (IMG_4918) - March 24, 2007, Rosko. Rosko, Gulcz, Wrzeszczyna: whoever rode the legendary route from Inowrocław to Krzyz - some 150 km in 8 hours - will never forget it.

Photograph 9 (IMG_4919) - April 16, 2011, Zlotow, railway station. Around noon the train arrived. No one got off and no one got on. He stood for a while and went back from where he came. I guess everyone from here had already left. The copy is made incorrectly. The image is reversed sides. I wonder if it makes any difference where the right side is...?

Photograph 10 (IMG_4920) - April 16, 2011, Zlotow, railway station. Two hours later, two teenagers showed up. They wandered aimlessly around the station. The trains were no longer leaving today. I used to not photograph on sunny days. I waited for "better" light. I didn't know when the next time I would be here. I did. I'm glad the sun doesn't bother me anymore.....

Photograph 11 (IMG_4921) - February 9, 2008, Wapno, water tower. I'm not very keen on going to shoot with others, especially photographers. Here I was with Witek before meeting Lech in Wągrowiec. We were in "his" Wapno. As promised, I did not photograph the mine. The tower is enough for me. Photography is an intimate activity for me.

Photograph 12 (IMG_4922) - February 9, 2008, Wapno, residential house. The day after my birthday and after returning with my children from winter camp, I was in "great" photographic shape and still that fog. I was not even surprised by the big pig living in the water tower and the number of windows in the owner's house.

Photo 13 (IMG_4923) - June 30, 2007, Ludomy. Road 178 - I have traveled it thousands of times by bus, bicycle, car. For a few years now I happen to stop and photograph a motif that I have passed many times before.

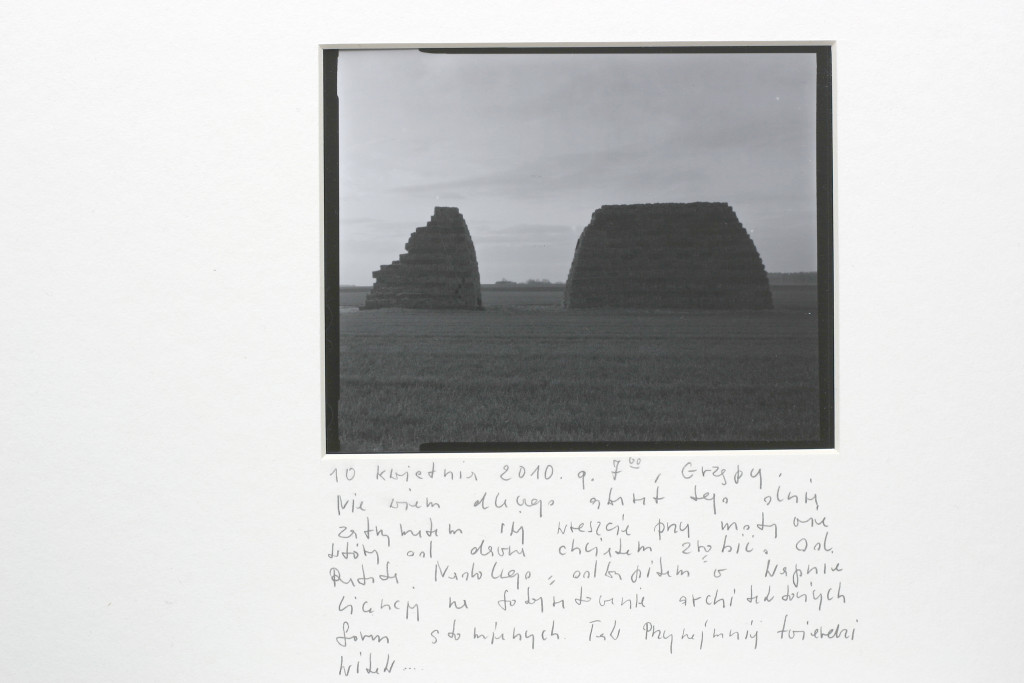

Photo 14 (IMG_4925) - April 10, 2010, 7:00 am, Grzępy. I don't know why it was precisely on this day that I finally stopped by a motif that I had wanted to do for a long time. From Rafal Nadolny I "bought back" in Wapno a license to photograph architectural straw forms. At least that's what Witek claims....

Photograph 15 (IMG_4926) - June 11, 2011, Sypniewo, granary. Thanks to my colleagues from Walcz, who were closer, I knew that there were such places as Nadarzyce, Sypniewo, and finally Borne-Sulinowo. However, I had never been there before. Imagination surpasses reality.

Photograph 16 (IMG_4927) - May 13, 2006, Czarnkow, bridge on the Notec River. After crossing the bridge to this day I still have the feeling that I am crossing the border of home, the threshold. In the past, going to Trzcianka, after the bridge I felt that I was already home. Today I don't know...

Photo 17 (IMG_4928) - April 12, 2011, Bzowo-Goraj. I've only been to the Bzowo-Goraj station once in my life: on May 14, 1981. We were on an open-air photography trip in nearby Lubasz, and from there, with my cousin Rysiek Szymczak, we set off at 4 a.m. to Gorzow, to a photography exhibition in Stilon. That was the first time I saw an exhibition of the events on the Coast in 1970 and 1980. + Wojnecki on canvas. It was a shock to me.

Photo 18 (IMG_4929) - January 30, 2007, Siedlisko. I arrived at this train station by train from Cross early in the morning. It was foggy. I remembered that it was to Siedlisko that I made my first ever independent trip by rail. I must have been less than 9 years old. I was going to my father's place, in the fields, to help pick flax.

Photo 19 (IMG_4930) - June 4, 2006, Wągrowiec. There are cities with water towers and there are non-photographic cities. Fortunately, Wągrowiec has a tower. It also has a bifurcation, which I don't know how to photograph. I'm saving the statue of the horse rotary for a better time....

Photograph 20 (IMG_4931) - June 4, 2006, Wągrowiec. On the cover of an album released at the end of the 1970s, titled "The World. Pilskie was depicted the beach in Wągrowiec. Compared to the photos inside the album, the photography was phenomenal. Shiny and colorful, like in a foreign resort. For years I thought that in Wągrowiec it was just like that... Years later I realized with some disappointment that it was just a photograph.

Photo 21 (IMG_4932) - February 9, 2008, Lime. Towers usually stand in the middle of cities and it is very difficult to find a good place to photograph them in a good perspective. In Wapno it can be photographed from all sides. A charming variety of.

Photo 22 (IMG_4933) - April 16, 2011, Zlotow. Zlotow has always been one of the most exotic cities in the province for me. One simply did not go there. There was no reason to. We were there once. It was probably in the Orwellian year. We went in a disheveled Nysa with Mr. King to receive an award at a local photo contest. As was often the case, our circle won all the prizes. As was often the case, we drank all the vernissage wine and I don't know how we got home. I think I had already begun rehearsing and preparing for "photography beyond consciousness".

Photo 23 (IMG_4934) - March 26, 2011, Tuczno Krajenskie. Tuczno Krajenskie, station on the Wałcz - Stargard Szczeciński railroad line. An important place. Here one used to get off when going by train to Betyn, via Pila and Walcz. Riding a bicycle from Trzcianka, one was almost there. Only a few more kilometers. Today the line is closed, like many in the region.

Photo 24 (IMG_4935) - April 16, 2011, Zlotow. The persistence of railroad infrastructure can be a contribution to a broader study of material culture, especially the "ephemerality" and short duration (disposability) of modern architecture. Solidly constructed railroad buildings, even without special "care," seem to be able to last forever, functionless absurd monstrosities. The astonishing contrast between the lack of function and the quality of the.

Photo 25 (IMG_4936) - August 19, 2007, Pila. First impression - the city after leaving the train station leaves no illusions about where we are. The militia-military character of the city could be felt at every turn. Depressing.

Photo 26 (IMG_4937) - August 21, 2007, Pila Główna. We took a bus to Pila, but often returned by train. We had to catch the last one, around 10:45 p.m. The next one wasn't until after 4 a.m. The night spent in a waiting room resembling the bow of a ship was an unforgettable experience.

Photo 27 (IMG_4938) - August 21, 2007 - A building near the Pila bus station. Everyone seems to have already left the house.

Photo 28 (IMG_4939) - August 20, 2007, Pila, signal box. Thanks to an invitation from Artur Lazowy to a workshop in Pila, I was able to wander around Pila with my camera for a few August mornings. Although my interest in historic industrial architecture was slowly dying out, I couldn't pass up on photographing this building.

Photo 29 (IMG_4940) - August 20, 2007 - Pila, a signal box. Apparently there are only two more such facilities in Europe. This, apparently, impresses no one. This object probably won't be saved either. Maybe, though?

Photo 30 (IMG_4941) - May 7, 2005, Czarnkow. The tank in Czarnkow has always been there. But there was never an opportunity to photograph it properly. Only the vision that they were going to "move it" mobilized me to action. This time I was not late. In Trzcianka we had our own tank. Obviously better and bigger than in Czarnków. I have it in the photo, but already without the barrel. While photographing it, I met a charming colleague, a construction foreman from Zofiow, who was willing to tag along in defense of the tank. We returned together to Poznan, where he worked. He taught me how to pull the plaster wet. When they moved the tank, he must have been in Poznań.

Photo 31 (IMG_4942) - May 28, 2011, Miroslawiec. One of the many symbols of the province. Here the reverse is shown. Normally the sword stood near the road and was visible from two sides. In Miroslawiec it was moved and placed in a square. Those entering the city, as if they didn't know where they were, were greeted by an inscription. Homeowners living in the shadow of the monument probably know where they are and don't need to be constantly reminded that they live in Miroslawiec. In 1848 in Dresden, during the riots, anarchists placed a painting by Raphael Santi, taken from the museum, on a barricade Sextin Madonna. They put the symbol of European culture on the enemy's bullets. They contented themselves with the reverse. An iconoclastic reversal and contempt.

Photo 32 (IMG_4943) - June 14, 2011, Lekno. Recent photo. The first rain in many days fell. I was in Lekno for the first time in 25 years. Lech and I were standing near some strange tombstone that had the eye of providence placed in the intersection of the cross arms. I couldn't think of anything. I knew the photo would fail. Twenty-five years is a long time. I exposed two leaves. I haven't developed the second one yet. Maybe someday... The rain was falling harder and harder....

Photo 33 (IMG_4944) - June 2007, Rychlik. Rychlik has always been a special place for me. Something like a black hole, non-being or antimatter. I have always had the feeling here that I am breaking into thousands of pieces.

Photo 34 (IMG_4945) - November 10, 2007, Rychlik. Gymnasium. Wanting is sometimes just wanting. Ruin may perhaps be the central metaphor My Province.

Photograph 35 (IMG_4946) - June 11, 2011, Sypniewo. In the field an impressive skeleton of a modernist structure. Architecture students should come here and, like in a dissecting room, learn anatomy.

Photo 36 (IMG_4947) - March 26, 2011, Tuczno. There used to be more murals in Tuczno. Only two remain. They were created in 1987, although I would give my head that they were there earlier. "Malczewski" was always the best in terms of workshop, although "Four" new and not covered by bushes was more impressive. As Zb. Herbert noted, a well-crafted work of art, even in a state of ruin or destruction, loses nothing of its quality and power of influence.

Photo 37 (IMG_4948) - March 26, 2011, Tuczno. The owner of the barn claims that it was his face, a coachman with a whip, that was immortalized by students of the Gdansk Academy of Fine Arts. He once tried to get someone interested in saving the murals, but gave up years later. He no longer cuts down the wild lilacs partially obscuring the painting.

Photo 38 (IMG_4949) - November 25, 2006, Trzcianka. The mausoleum next to the defunct city hotel and Gulka are the most exotic places in my city. As children we believed that Soviet heroes, liberators of Trzcianka, were buried there. The place was sacred and magical. We avoided it and it never occurred to anyone to enter it. The taboo was also observed by adults, they drank beer in the squares paying respect to the place. After 1989 I defended the mausoleum from radicals and patriots. Today I have my doubts. An architectural form without an idea is an empty sign. It means nothing.

Photo 39 (IMG_4950) - April 17, 2010, Czarnkow. The first KSK bus from Trzcianka to Poznan was leaving at 6 am. It reached Czarnkow after 25 minutes. It did not move on until 7. It seemed to stand an eternity. If there was an empty seat, I always sat on the right in the third row. I woke up and always saw the same view. The walls around the market were covered with green dots a few centimeters in diameter. The raster made a spectacle. A girl in a meadow was emerging from the morning gray. A psychedelic vision outside the window of an overcrowded, cold bus.

Photo 40 (IMG_4951) - August 20, 2007, Pila. Wandering around Pila with my camera on an August morning, I never imagined that this would be the beginning of an expedition into the depths of the Pila myth. A search for identity, memories and sentiment. Most of the time, an exhibition is a summary of work on a subject. In this case it is exactly the opposite. This is just the beginning of an expedition into the depths of time and places... into the depths of oneself.

Photo 41 (IMG_4952) - April 20, 2008, Walcz, waterworks. The tower was bought by a local architect - an enthusiast who assisted me during the photography. He necessarily wanted to persuade me to jump on the reservoir together. Apparently the feeling of "king sajzu" priceless. Maybe another time...

Photo 42 (IMG_4953) - April 12, 2008, Walcz, PKP. In the spring of 2008 I organized several trips to Walcz. From Poznań by KSK bus the route of about 120 kilometers is covered in three and a half hours. One can recall a lifetime...

Photo 43 (IMG_4954) - April 20, 2008, Walcz. Nitragina, the name of the distillery and sailing club. We often went here for regattas. Sometimes we managed to win against the Juszczak team. At that time there was no law on upbringing in sobriety. Spiritual patronage of spirits did not prevent anyone from shaping the sportsmanship of young people.

Photo 44 (IMG_4955) - June 11, 2011, Walcz. Monuments relating to the mythology of the Pomeranian Wall are generally preserved in better condition. It is apparent that they are part of the still living tradition of the capture of the Pomeranian Wall. Without sociological research, it is difficult to decide unequivocally how "Grunwald" swords are perceived by residents of the former Pilsen province. They certainly constitute an interesting architectural phenomenon on a national scale.

Photo 45 (IMG_4956) - May 28, 2011, Wronki. For those outside our cultural context who do not recognize "Grunwald" symbolism, swords can be read as crosses. For example, the very similar finial of the Poznan June 1956 monument in Poznan. Accustomed to roadside crosses commemorating accident victims. Travelers still may associate these places in a different way than intended. The thesis requires proof.

Photo 46 (IMG_4957) - April 20, 2008, Walcz, Radun Lake. The entrance to the ruins of the workers' hotel. The view of the lake could envy many high-class tourist facilities. I remember that in elementary school they used to scare the more reluctant students with the Workers' Huforce in Walcz. It often helped...

Photo 47 (IMG_4958) - April 20, 2008, Walcz, PKP. It rained all the time in April 2008, certainly when I was in Walcz. The city, which I always visited in the summer, I always perceived positively. Probably due to my colleagues from the Technical School living here, joint fishing trips, etc....

Photo 48 (IMG_4959) - April 20, 2008, Walcz, a former hotel. Next to it stands a large, empty, four-story block of flats. A large family lives in an adopted garage or workshop. As the equipment was being set up, the door opened and the residents began to come out one by one. A sizable bunch of young children under the care of an older brother. They were festively dressed. I think they were going to church....

Photo 49 (IMG_4960) - April 20, 2008, Walcz, Grain Works. There is no direct rail connection between Walcz and Trzcianka. One had to travel with a change of trains in Pila. Covering 28 kilometers sometimes took many hours.

Photo 50 (IMG_4962) - April 16, 2011, Podgaje. Along the main roads leading deep into the territory of the former "Province" stand monuments to this day. Two jointed concrete swords on a pedestal. Between them, about halfway up, a coat of arms cartouche with a white eagle, originally made of concrete. In many places it has been replaced by a plastic molding. The inscription "voivodeship" still survives in several places. In contrast, the inscription "pilskie" has been removed everywhere without exception. In the northern part of the former Pilsko, the same form marks places associated with the history of the battles and the capture of the Pomeranian Wall. Such a dual use of the symbol may indicate a desire to transfer the "liberation" ideology to the entire area, not only the Pomeranian Wall, but also places completely unrelated to this tradition, including near Wronki and Oborniki.