Nicholas Winter: Warsaw - One-Dimensional Landscape

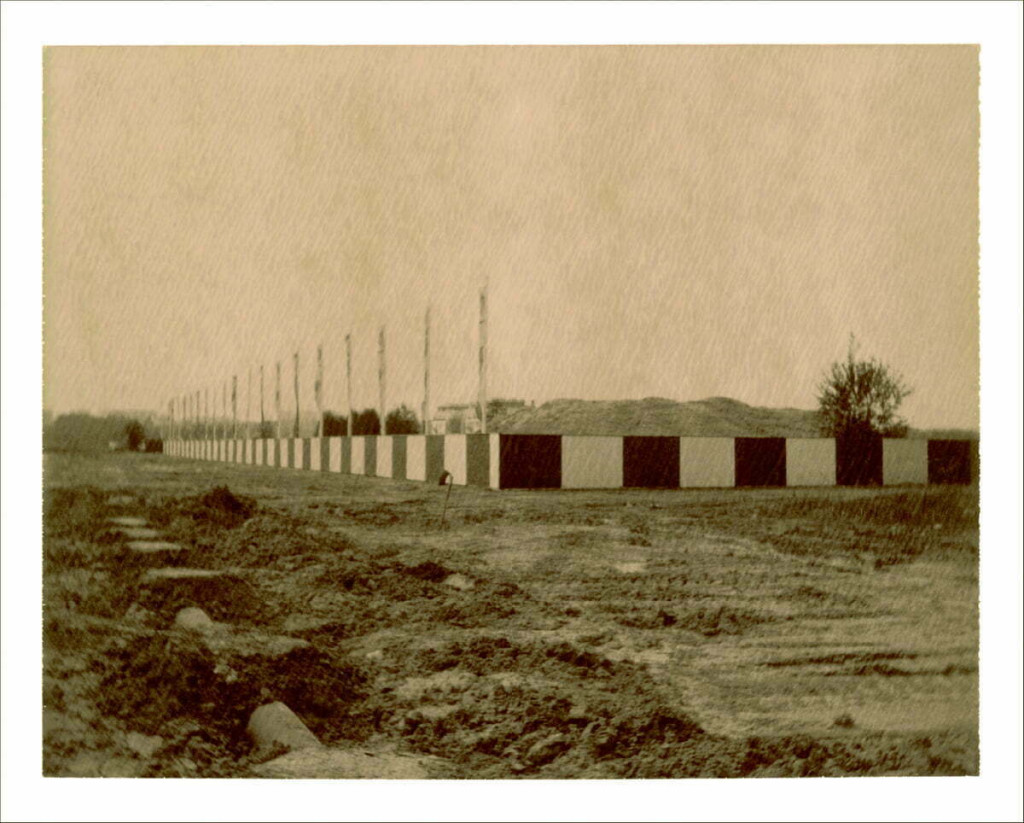

Communist Poland is associated with gray: gray people in a gray landscape. Gray concrete facades, advertising signs in dull colors, no lights on the streets, monochromatic clothing made of poor-quality materials, ugly paper packaging. This atmosphere is documented - already in the new reality - by Nicholas Winter's sepia Polaroids

(b. 1973) from the "New Wilanów" series (2009).

Poland after 1989, the Third Republic, is primarily an explosion of color. The ubiquitous advertisements inscribe the country on the Vistula River in the global village. The eye-popping vividly colored packaging - a symbol of the "rotten imperialism" hated by the communist authorities - the neon signs, fancy clothes and makeup in no way resemble the image that Western Europe had (and in many cases still has) of the countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Cold War homelands. Western photographers visiting Poland "after the breakthrough" have long since revised their perceptions. The best example of this is the (improbable) colorful works by American Robert Walker.

English photographer Nicholas Winter sees Warsaw in a completely different way. His Polaroids from the "New Wilanów" series are notes from the new Poland evoking the spirit of the People's Republic of Poland. The monochromatic images of newly-built apartment blocks are reminiscent in style of photographs documenting the rebuilding of the capital in the 1950s and 1960s. On the one hand, this is certainly due to Winter's use of a Polaroid 320 land camera, popular in America and Western Europe at that particular time - and the use of a special "chocolate" edition of Polaroid film in the series from Wilanów. On the other hand, however, the climate of those years resembles the motif itself: sprouting up like mushrooms after the rain, the new buildings are merely a more modern variant of the boxy architecture of the People's Republic of Poland. The difference lies in the invisible forces at work: while then the authorities, in accordance with the Marxist doctrine of social equality, placed representatives of the most diverse social strata in block housing, in the capitalized country society itself is divided into classes. Depending on one's level of wealth, one can now live in better or worse blocks of flats, but one can also move to villas (the name of Warsaw's southern district, Wilanow, is "Villanova" in Italian). The regime of the People's Republic of Poland, like that of other Eastern Bloc countries, was based primarily on preventing its residents from moving. The pursuit of total social control (as in Orwell's "1984") was expressed in the effective restriction of citizens' mobility. It was not only impossible to travel freely to the West, but also to change the place of residence assigned by the authorities. Since the institution of rental housing did not exist at the time, the only way to change your place was to sign up for the list of a housing cooperative and wait your turn.

Contemporary Wilanów is one of the more affluent, albeit peripheral, districts of Warsaw, associated with the "Polish Versailles," as the 17th-century royal palace, one of the capital's main attractions, is sometimes referred to. Winter's photographs, however, are completely stripped of the royal aura. In a surprising way, he seems to be using his works to reinterpret the value of the transformations taking place in Poland. The new suddenly turns out to be the old: Corbusier with a capitalist face.

Such a subversive depiction of Wilanów is reminiscent of the way Swiss émigré Robert Frank documented the changes in postwar America. However, while in Franek's The Americans (1955-56) - an album that mercilessly disavows the vision of "The American Dream" - the main protagonist is the inhabitants of America, the protagonist of Winter's work is the dwellings of Poles. The few human figures in the Wilanów series seem to be alienated and completely subordinated to the surrounding architecture: a lone cyclist crossing an empty intersection, a boy with a dog crossing an empty roadway, a woman with a baby stroller fitting into the rhythm of the blocks of flats behind her. The coexistence of the human figure and architecture is not a given in Winter's depictions. Man seems to disturb the perfection of the "arrangement" with his presence. In one of the photos, a woman standing under a billboard advertising the next phase of architectural investments in Wilanów resembles so much, along with her surroundings, what is depicted in the advertisement, that the levels of imagery are blurred: in the photograph both realities become equally unreal. The style of the writing on the billboard also resembles more the period of communist housing cooperatives than contemporary development solutions.

Winter also looks for disturbed symmetries within the buildings themselves - he is primarily interested in what is left unfinished: the foundations of the new blocks jutting out of the ground and reflecting in the water are reminiscent of Daniel Buren's truncated columns from before the Palais Royal in Paris. Even in the "finished" landscape Winter finds curves, irregularities. The horizontal lines of balconies escaping to the horizon do not meet at the point of confluence in his depictions, and the axes of symmetry delineated by the cranes are always shifted more toward one edge of the photograph.

Because of his strong geometrization of the architectural landscape and his work in series, stylistically the closest reference for Winter's photographs is Ed Ruscha's conceptual depictions of the 1960s. Winter looks at the surrounding reality through its reduction to main lines and forms. In Wilanów, he sees ducts of identical balconies and windows, rows of street lamps, intersecting lines of smooth streets, evenly trimmed lawns and sidewalks lined with new paving stones. This peculiar geometry seems to be nothing but a new (nouveau riche) form of universalization of life, as if the Polish landscape is heading towards a voluntary reduction. Man, who is almost absent from Winter's photographs, is illustrated in them by his place of residence: a one-dimensional man - as Herbert Marcuse warned against in the 1960s - an element of the masses, accepting imposed (or offered in a more inviting package) forms of daily life and entertainment, manipulated by the new forms of marketing as effectively as by the old dictatorship.

Nicholas Winter (1973), a British photographer born in Germany, studied fine arts and photography in the UK. Since 2002, he has lived and worked as a freelance photographer in Basel. As he travels, he documents the situations he encounters in a distinctive style, extracting a kind of melancholy atmosphere from the technical (chemical) qualities of photography. In 2009 Winter spent several months in Warsaw, where he made the Polaroid series presented above.

www.nwinterphotography.com

Robert Walker, Colour Is Power, 2002

Herbert Marcuse, Der eindimensionale Mensch, 1967 (Polish edition, One-Dimensional Man, translated by W. Gromczynski, 1991). Earlier works by Winter were reproduced by "Fotografia Quarterly" in issue 18/2005.

The article appeared in No. 32 of "Kwartalnik Fotografia" in 2010