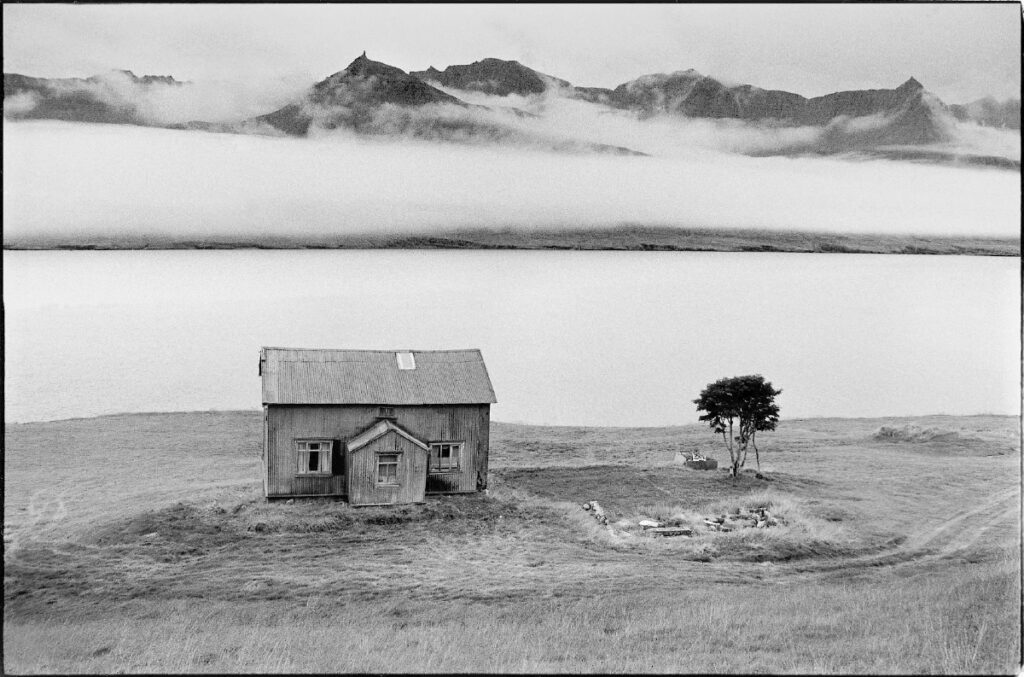

Nökkvi Elíasson's surreal landscapes

Danish writer Peter Hoeg wrote that any room serving some form of community abandoned becomes unreal....

Kiljan Halldorsson

- I am an amateur photographer living in Reykyawik. I started my photographic career 20 years ago, mainly focusing on black and white photography. During the last decade, I focused my photography on abandoned farms and other abandoned dilapidated buildings," is how Nökkvi Elíasson writes about himself on his website.

And he is absolutely right - he is an amateur photographer, in the latter, better sense (the former is the antonym of professional), in which an amateur is a lover, an enthusiast. I have absolutely no idea how it happened that he started photographing abandoned farms, but the set he created gave him a fairly strong position in Icelandic photography, gave him fame, culminating in the publication of these photographs in book form.

What strikes you when browsing through the album is the shrill emptiness - like that of the surrealists; there are no trees, no other buildings, no people, no fences, no electric traction poles. Nothing, just sad, lonely and abandoned individual buildings blending into the unforgiving Icelandic nature - leaden skies, bare rocks and dried lichen grasses. It's a bit like visiting the moon... Looking at Elíasson's photos, one wonders, is it possible that people once lived in this place?

Admittedly, Nökkvi uses an analog camera, but he makes some interference with the "natural" recording process, namely, he very often uses a dense red filter, which results in an almost black sky. In this way, he fits into the so-called FIAP aesthetic, full of - to use the jargon of photographers - "FIAP halftones," which is supposed to increase the drama of the performances. In my opinion, this procedure is completely unnecessary, since the reality captured by him is poignant enough on its own and does not require any embellishment. I am also grossed out by the rolling verticals in some of the photographs, which are the result of the unskillful use of wide-angle lenses. All of this indicates that the author is suspended between two conventions - documentaryism and aestheticism (quite sterile); it is unclear whether he is more concerned with visually appealing images or the message. This, unfortunately, we do not know.

I have long searched for an answer to the question of what the message of the series is: is it a cry for the preservation of abandoned buildings (because, after all, they are also a cultural legacy of Iceland), or is it "just" an expression of the photographer's admiration for the surreal landscape? I do not undertake to answer.

Photographs courtesy of the author.