Transparency - about the photography of Eva Rubinstein

...which is impossible to talk about, This is something to keep quiet about....

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus logico-philosoficus

Eva Rubinstein's photographs are transparent like water in a mountain stream. They are also transparent (diaphanous) like a tranquil lake, where through the reflection in its surface something unseen peeps through from the depths. And just as the water in an agitated stream blurs the shapes of the stones inside it, the mirror of the lake tempts the eye with the reflection of the exterior, as if they (the stream and the lake) do not want to give out the secrets they guard. The beautiful young Narcissus enthralled by his reflection tried to touch it, but only dipped his hand and made a momentary confusion in the - seemingly permanent like himself - beloved shapes. With Narcissus' experience in mind, the photographer (artist) can take up the challenge of transparency, i.e. maintaining harmony between glass and mirror, interior and exterior. The condition is one: one must have enough humility in oneself to barely shine through from outside the reflection of reality that fills the image. Such an attitude could suggest spiritualism, or even religiosity, were it not for the fact that in layman's speech the same sense is expressed when talking about feelings, conscience, ethics, or moral responsibility. Eva Rubinstein belongs, in my opinion, to the small group of diaphanous photographers who are able not only to perceive, but also to effectively express with the silence of an image the most intimate, important moments of the stream of one's life: raptures and joys, as well as sorrows and despair. Eva does not seem to pose questions with her photos, although there is always that elusive, undefinable, unguessed something in them, which, like music, can soothe or disturb.

These photographs, like miniature Japanese haiku, are silent about fundamental issues, they are confidences of the non-obvious, where despair is not necessarily shrouded in darkness, and luminosity can express the bitterness of human, individual fate. For Eva speaks only on her own behalf, although she speaks of universal issues: above, beyond,

or perhaps even pre-temporal. The singularity of her work - by its uniqueness - makes it a temple of inner truth, the existence of which dark forces have no faint idea, because into these spaces of privacy they have not, do not and will never dare to enter. They won't, because it is not a brick temple of deity worship, but a delicate, living temple of art, wisdom and faith in truth, protected by the interior of the artist. The magnificence of this temple will be revealed to the world through his works.

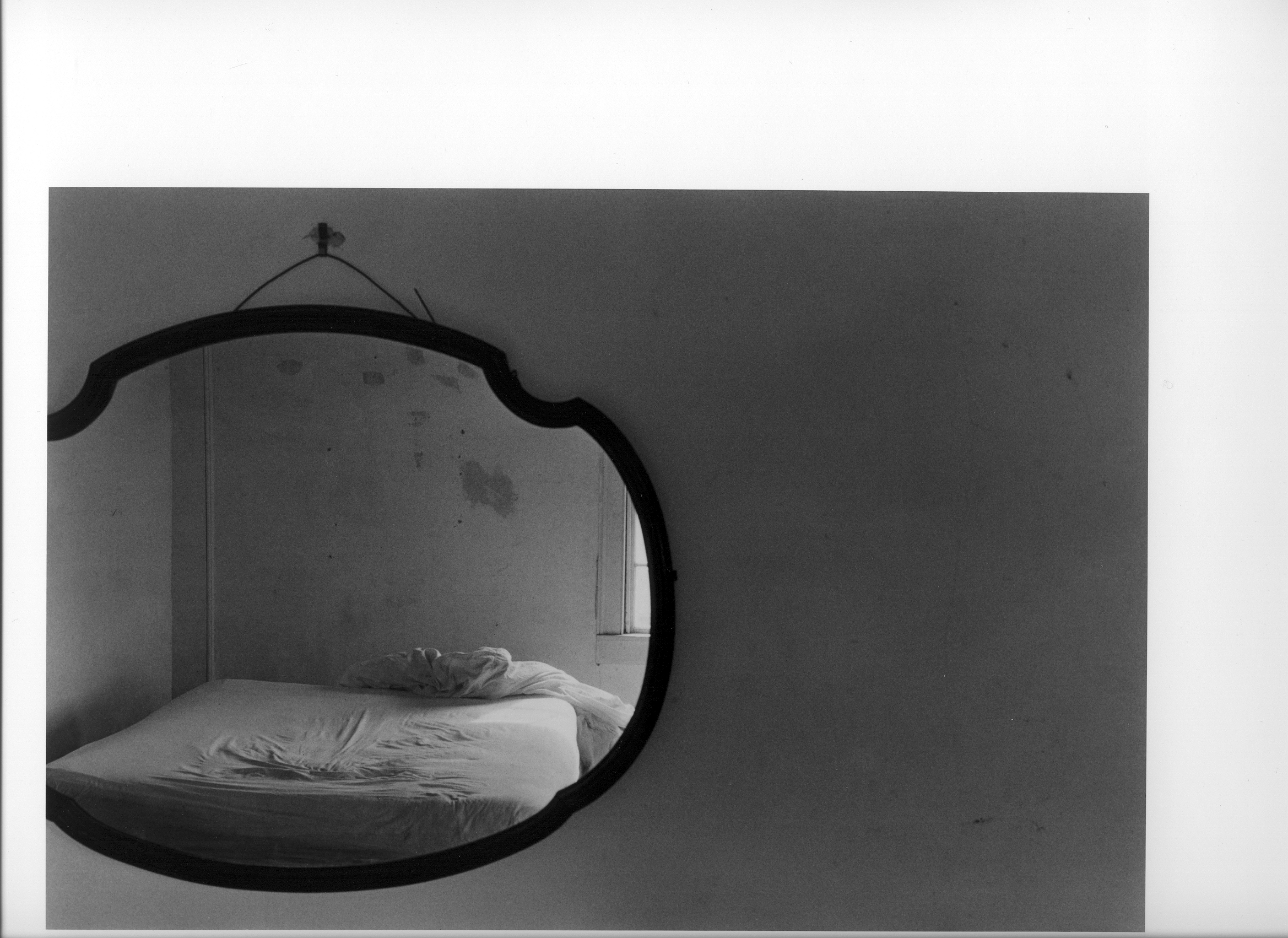

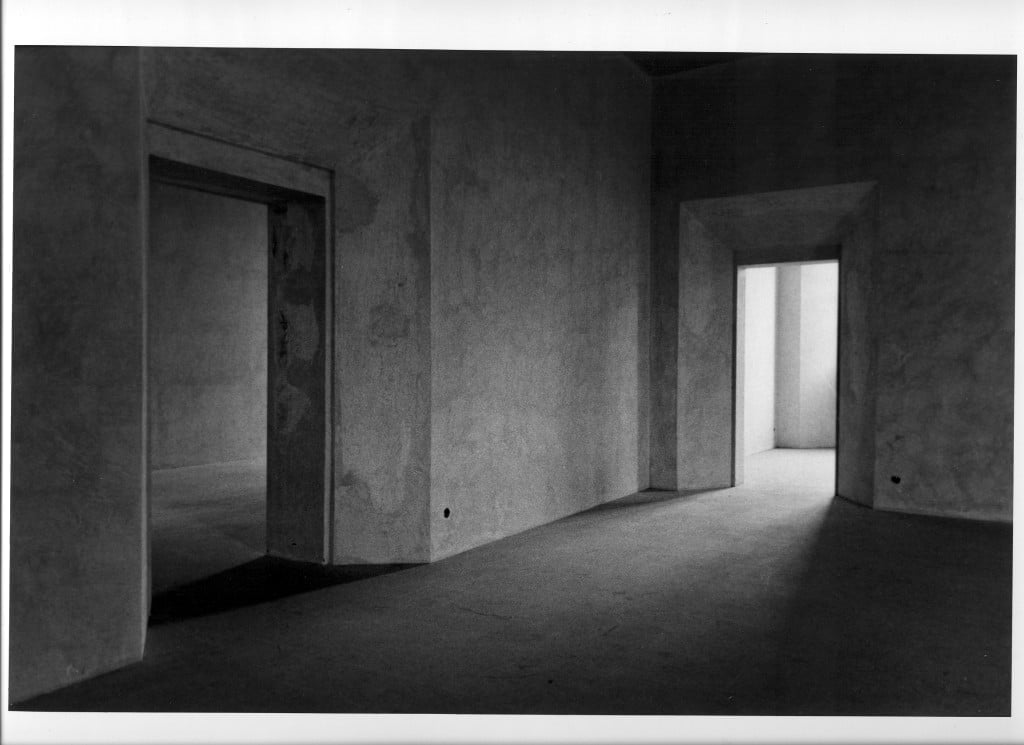

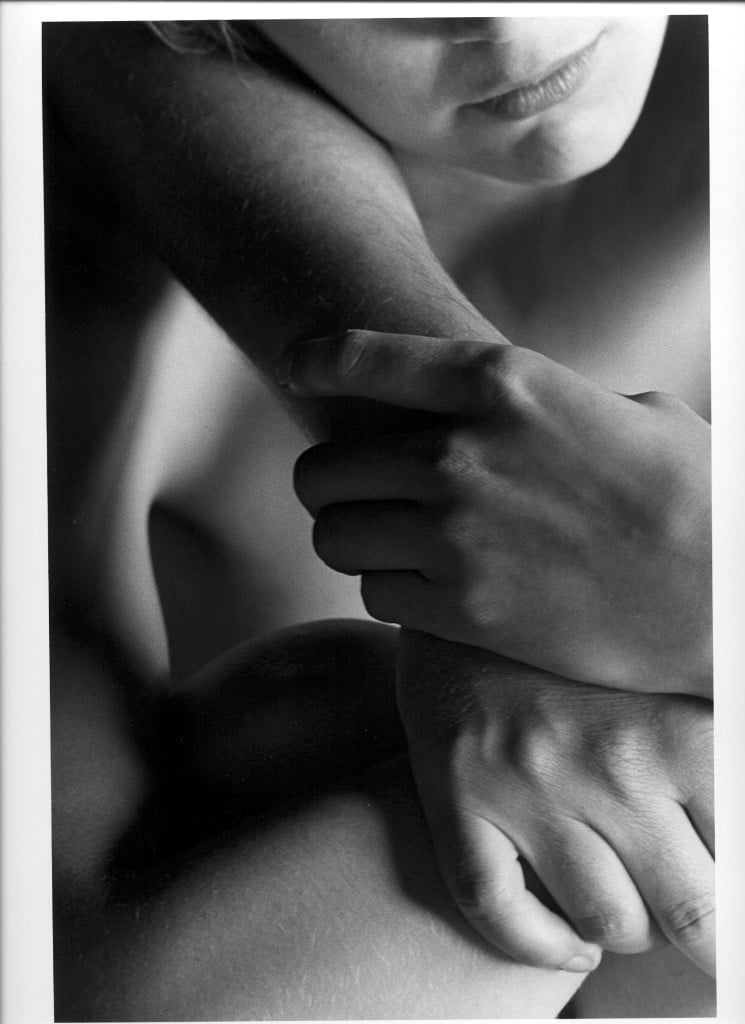

The selection and arrangement of the photographs for this book were made by the author. It opens with a solitary photograph of a hotel lobby, where curtains smoked by a gust of wind float above the man-deserted armchairs like luminous, gentle ghosts. I got the feeling as if something seeped into this interior and through the photographs reached all the way here to me: into another time and into another distant reality. What I felt when viewing it for the first time is still returning today with equal force. This photo will never grow old, because it was taken by the spirit world, which is unaffected by the passage of time, because it is of the immaterial world - and therefore eternal. Human beings, inherently mortal, can only prolong the memory of themselves, and the most beautiful way to do this is to love art and that part of earthly life that is ruled by love. Perhaps that's why Eva put most of the photos together in pairs, between which there are secret relationships in spite of the differences in time and space - the dates and places where they were taken. It's as if she let herself be carried along by life like a drop of water by a stream that will lead her from source to mouth anyway. Because there is always enough to know both shores of time, one just has to believe that when the current brings us there, it will be the right place and time. In Eva Rubinstein's photographs one can find everything that constitutes life, death and love. They are imbued with hope, expectation, motherhood, loneliness and doubt. There are many ajar, waiting doors, windows, barely abandoned and still warm beds, mirrors reflecting a world swapped sides. There is also a dormant merry-go-round, as if life has gone to rest for a while, there are heavy wooden trunks unfit for the final journey and a fountain face crying with living water. There is the packed, dingy piano in Chopin's home in Zelazowa Wola, as well as Father Arthur's back sitting in front of the piano. There are the poet's hands and Eva's self-portrait, in which some mask tries to replace her own image. There are also cemeteries, staircases leading one doesn't know: up or down? There's also a maze of walls and walls, the most enigmatic of which is the one photographed at night, with a bright ladder attached, as if someone decided to check out what's obscuring and wouldn't or couldn't return. In addition to many others, there are my especially favorite photographs: the entwined (1977) and the lying (1970) couple. Because there are some photographs about which it is impossible to say anything, one can only remain silent along with them....

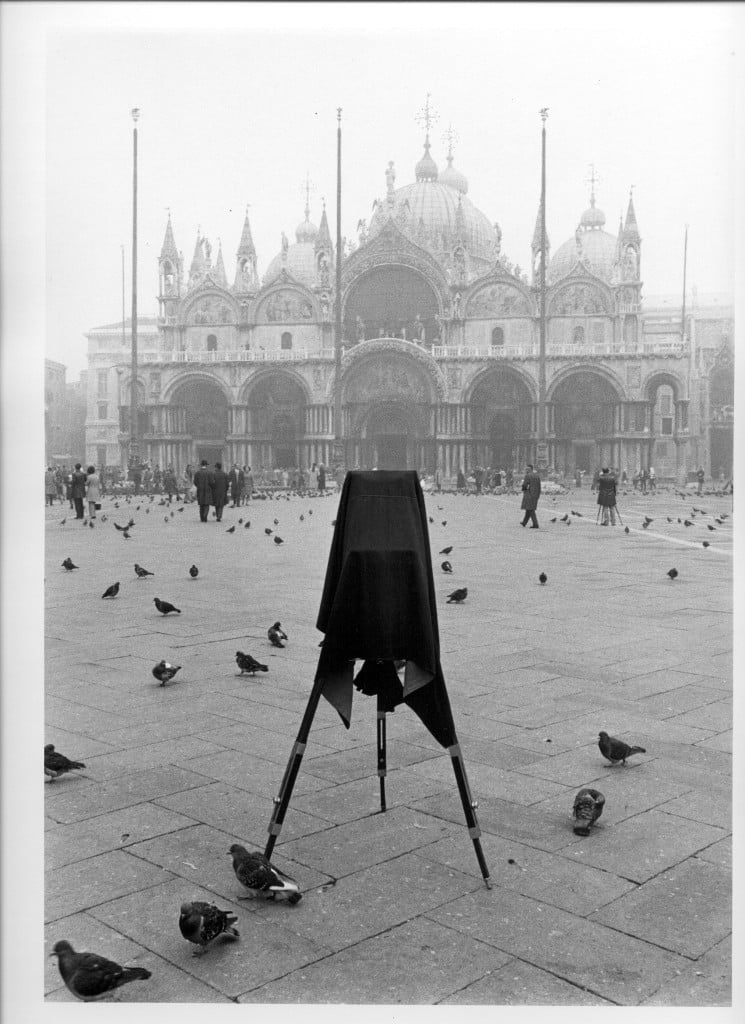

A lone photograph also closes the whole thing. It is one of Eva's older photographs (1970): a large-format camera on a tripod shrouded in black canvas in St. Mark's Square in Venice. Eva's placement of it at the end probably has a symbolic meaning. I dare to suspect that it is both a whisper of gratitude to photography and a symbol of parting with it, for Eva stopped photographing a nice few years ago... I would like to take this opportunity to thank Eva for being there and for her photographs, which have made me feel not completely alone on my artistic path.

The text is an introduction to Eva Rubinstein's book, Photographs between 1967 and 1990, Dot Publishing, 2003. It can be purchased at our online bookstore, the KF Gallery

Paris, March 10, 2003

Eva Rubinstein - was born in 1933 in Argentina during her father's concert tour, as the daughter of Aniela Mlynarska Rubinstein and her husband Arthur, a pianist. During breaks in her travels, she lived in Paris. At the age of five, she began ballet dance lessons with Matilda Krzesinskaya. After the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the family emigrated to the United States. In New York, she danced in a ballet and later performed as an actress (Dybbuk, Three sisters, the first performance on Broadway The Diary of Anne Frank). She married pastor William Sloane Coffin. She gave birth to three children. After her divorce in 1968, she took up photography. For a short time she was a student of Lisette Model and Diane Arbus. During a period she did commercial work(press, documentary, portraits, photos for annual reports of companies) after which she turned to photography of a personal nature. Since 1970 she has exhibited all over the world, between 1974 and 1990 she conducted workshops in the United States and Europe. She has published 3 limited-edition portfolios, 4 monographs (Morgan and Morgan, 1974; Fabbri, 1983; Kropka, 2003; Zhejiang Photo Press, 2018) and an album Lodz: Instant Meeting (ed. W. Grochowalski, Lodz 1998).