Vintage photography and the modern viewer

Reflections on the occasion of the exhibition Salle Jaffé (1845-1920) at the National Museum in Poznan - November 7, 2021 - January 30, 2022, curated by Ewa Hornowska. The article appeared in two parts - in "Kwartalnik Fotografia" No. 40 and 41.

Part 1

Presentations of photography, the most popular medium today, are a very important part of contemporary culture - as much the mass one as the elite one. At least since the late 1970s, when the publication of the On photography Susan Sontag1, awareness of the saturation of the surrounding world with photographs was becoming widespread. In recent decades, sociologists have diagnosed that we even live in a "photosociety"2. In creating an exhibition of photographs, the need to learn from the deluge of uncontrollable photographic production of modern man therefore seems obvious. Photography is a social phenomenon, also because of its documentary nature, including - historical photos. We have at our disposal nowadays impressive tools to enable the viewer to read in such photos their old, but also new meanings. Then the old photography becomes readable, fresh and irresistibly interesting even for laymen. The impulse and the canvass for my reflections on this subject became a presentation at the Museum of Applied Arts in Poznań in 2021/2022.3 the work of Salle Jaffé, a leading personality among photography enthusiasts in late 19th- and early 20th-century Poznan.

Exhibition curator Ewa Hornowska published 115 photos in his monograph4 - a not insignificant, though unspecified part of his work. This is as much as can be found in the collections of two Poznan institutions and as much as has been found in publications from the photographer's life, cataloged by her and - which Hornowska does not mention - two other Poznan researchers Magdalena Warkoczewska and Ewa Stęszewska-Leszczynska5 In the collections of the National Museum (about 100 photos6) and the University Library (637), in addition, as reproductions in magazines and other professional publications. The photos are also with the City Historic Preservation Officer, but have not yet been extracted8. The Museum and Library's collection contains prints of the same photographs in many cases, so the 115 frames given above are ultimately known. About 30, or a quarter of this recognized portion of Jaffé's extremely interesting oeuvre, were presented at the Poznan exhibition. The show was therefore intimate, nevertheless tentatively representative of the whole, given that a monograph on the photographer was published at the same time. Unfortunately, communication with the contemporary viewer was lacking

The exhibition was based on the presentation of originals (about 30) - not large and undoubtedly sensitive. The latter must have determined the manner of lighting and the atmosphere of the room, intended for this presentation - gloomy. The audience was not made any easier to see the fascinating views of the city and its inhabitants from more than 100 years ago, as were the suburban landscapes. Instead, a fragment of a historical map of Poznań, on which visitors were supposed to find the addresses of the places shown by Jaffé in the presented photographs, deserved a huge enlargement, occupying entirely one of the walls of the exhibition room. But even this was managed by few and with difficulty (the map has not been modernized).

What was missing for the final evaluation of Jaffé's photographs, however, was an indication of the techniques in which they were made. This applies to all of the surviving works (more than 160), including landscapes, omitting one identified as dichromate rubber9. The description of the surface of the papers in the aforementioned monograph does not solve the problem, we should know the chemistry of the photo - whether it is a gelatin-silver print, gum, pigment, heliogravure, platinotype and so on. We do not know if the author originally used the older collodion or albumen technique. Leaving aside the relevance of information about the photo's technique for the conservator or those setting storage conditions, this knowledge was of paramount importance to Jaffé, its acquisition was an intellectual adventure. I will write more extensively about this in the next issue, here I will hint that this must have been what influenced him to seek contact with the Berlin photochemist Hermann Wilhelm Vogel and the Poznanian's membership in the first renowned photographic societies: the Vienna one (from 1891), the Hamburg one (from 1892), and finally the Berlin one (from 1894). He intensified his work on noble methods precisely from the time he entered these circles and published in their press organs on the topics of color techniques10. The curator of the Poznan exhibition writes that the photographer even specialized in them11.

Meanwhile, old photographic techniques, even the simplest ones, but from before the digital era, are the subject of much interest in various workshops of so-called analog photography; its magic is so great that classes in the photographic darkroom are sometimes used as socializing, therapeutic. Noble techniques require patience, accuracy, rehearsals, noting results and endless repetitions; they have never allowed the same effect twice - something uncommon in the "copy-paste" era. They are interesting by chemical processes, materials. As well as other ancient techniques. For example, for an albumen print, a layer of gelatin is prepared by simply beating a hen's egg with table salt. Such things are worth showing in the exhibition (as a video from the photographer's studio), in related workshops, even in its digital trailers. The viewer, brought up on Youtube instructions, appreciates a short message - audiovisual or direct, as the National Museum in Poznań, of which the Museum of Applied Arts is a branch, is well aware. Since recently, the MNP has been advertising itself with successful podcasts12.

Jaffé was well prepared for the practice of photography almost from the moment he began to leave his first testimonies of it. The class of these and later photographs, documenting urban objects, the skyline , can be compared to Emilia (Balbina) Mirska's photographs from her album of views from the flood of 1889, and considered a continuation of a similarly reassuring aesthetic and philosophy. They were still being used in 1907. Jaffé, when, like Mirska, he used large-format cameras that saw the image upside down and, in addition, in mirror image. The scale of the difficulty of capturing the intended frame was incomparable to what today's photography enthusiast knows. But most impressive is the spatial depth and sharpness of detail achieved by the large glass negatives inside the new synagogue. In turn, this is of value to the modern viewer.

In 2003. Sontag drew attention to a new phenomenon: photographs placed in the press as editorial material were not aesthetically different, sometimes also in content, from the adjacent advertising photos13. This dulled the viewer, demolishing his sensitivity probably more than the phenomenon of the flood of photographs itself. All the more so in the exhibition of ancient photography, the principles of advertising (originally called propaganda, by the way) can and should be used to make historical photos attractive and intensely absorbing to the modern viewer.

So we should present museum photos like advertising - similar setting, format and ease of viewing. What probably repels most today, especially the young, is the difficulty. Hence, for example, the difficulty of using noble techniques or photographing with a large-format camera is "sold" only as a curiosity-inducing novelty, an unknown possibility (as I pointed out above). On the other hand, the exposure of photography, especially old photography, absolutely must be convenient for the viewer and quickly act on feelings. Patiently looking at small original prints, the over-50 generation will be determined, but the waning eyesight will take the pleasure out of it for them as well. The most famous photography galleries have a few common display principles:

- photos are well lit

- if the condition of the original precludes adequate illumination, also if the original is small, an illuminated reproduction of convenient size and possibly an underexposed original is presented

- objects hang at eye level, or if not, in a large enough photo format to be viewed at another level

- The exhibition has dominants from enlarged photographs (mostly contemporary reproductions) that help convey the essential message of the photographer and curator.

All of these rules can be encapsulated in one:

We show so that you can quickly see, understand and feel.

Earlier it was used by the creators of the installation, which was the most famous photo exhibition to this day The Family of Man in 1955 (ob. World Heritage Site14). The nature of the manifesto of peace and equality for all people, as conceived by photographer Edward Steichen, was realized through the selection, format and captivating arrangement of photographs. Hence its consistent and emotional message, reaching more than 10 million visitors around the world, from both the so-called Western and Eastern Bloc. Today, the principles outlined above are applied by the most important photography galleries and museums, from the Museum für Fotografie and Martin-Gropius-Haus in Berlin, to the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) and the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, to the Carla Sozzani Gallery in Milan15. The Museum of Photography in Krakow is also implementing it in a new form, allowing reproductions (e.g. from greeting cards)16. The Poznan MNP in its branch, the Ethnographic Museum, also decided to due to the value of archival photos, and for the sake of their good condition in the future and in accordance with conservation requirements , according to the organizers, to show (successfully) during the exhibition Black on white in color (2019)17 large reproductions of old photos, in addition, adding color to them!

Going back to the sources, to The Family of Man: significant that it presents documentary photography. The question of whether such an unprocessed version of it is art became obsolete by the 1920s at the latest. German art historian Wolfgang Kemp argues this point, quoting one of the early modern photographers Paul Strand:

The discussion on the question of whether photography is or is not art (...) has contributed to the fact that, fortunately, no one knows exactly what is art. The word no longer passes so smoothly through the mouths of reasonable people. And some photographs fortunately show that the camera is a machine, and quite a wonderful one at that18.

A document, in the face of the limitations imposed by so-called art photography, is an open form; it often has more meanings than those envisioned for it by its author, and is read differently at other times, allowing other conclusions to be drawn. Ruth Jacobi's photograph of a procession of Poles in connection with the 1918 District Diet in Poznan, which I found in her legacy, shows that it was not at all constantly raining at the time as has been reported so far, and that the crowd was walking down Berlin Street at ten to four in the afternoon, as can be seen on the street clock19. A document of this kind with large enlargements also reveals new details. An exhibition of Jaffé's work featured a photograph by Margarethe Schreiber, his prize-winning colleague at the photographic society. The postcard-sized work is part of a series of shots from the 1904 Corpus Christi celebration in Poznan, delighting in the elegance of life, which is now in vain, and in the details - from the multitude of sunshades, store signs, and the richness of the facade decorations (including birches on the balconies), to the closet and faces of the participants.

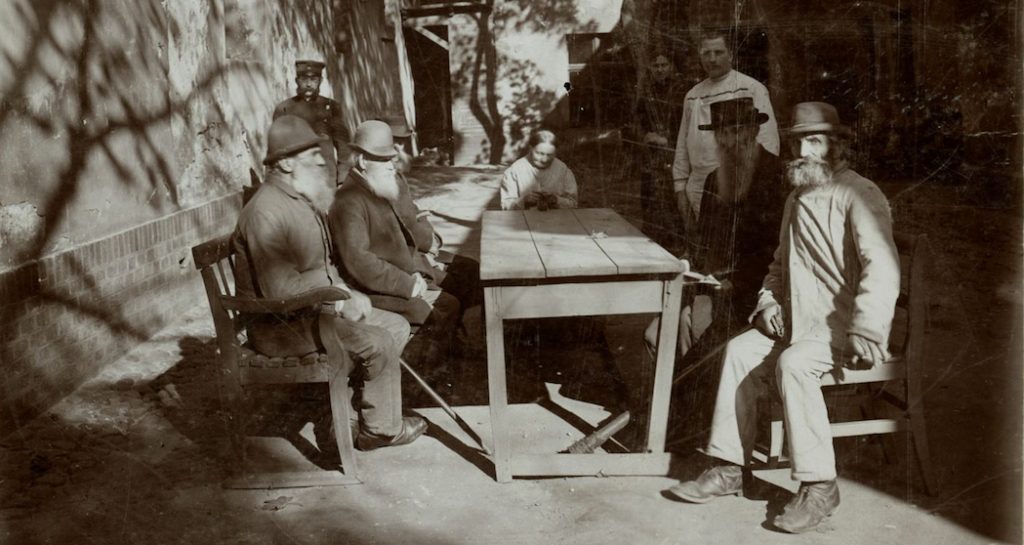

The man in the photograph brings life. That's why, among Jaffé's surviving photographs, the ones from the shelter stand out - just three shots, taken in the same place, but with the sun streaming broadly into the long courtyard and illuminating the precarious old people. Each figure is a separate story, read from silhouette and gaze. One could study them for long minutes if one chose to exhibit the large-format enlargements, even for an entire wall, that modern technology allows one to make from glass negatives (and these do exist). Schreiber's postcard photos, although we only have prints, can also be reproduced to larger formats - and only then will the incredible amount of detail be available to viewers, and the photograph itself become a tool for them to learn about the old world.

A good exhibition of old photography requires conditions for good communication with the viewer, taking into account the consequences of the emergence of a "photo society" and the role of advertising in image consumption.

Part 2

A tool for learning about the world. Photography by Salle Jaffé (1845-1920)

Photography conceived as an intellectual practice seems to have something in common with conceptualism. It sounds dangerous to those who value photography faithful to its particular technique and documenting reality, even if processed. However, 120 years ago, these three elements could be reconciled, as the case of Salle Jaffé first illustrates.

He came from an incumbent Jewish family in the city, having traded in timber for generations. He was one of Poznań's most important entrepreneurs in this industry at the turn of the 20th century. While enjoying a high material status, he also developed an intellectual one - in his passion for photography, of which he became a passionate lover and practitioner. It was thanks to it that he took the position in the social hierarchy that intellectuals enjoyed. Suffice it to mention that in Poznan, another well-known Jaffé, was, among others, a lawyer and also a timber entrepreneur, Moritz. He was passionate about history and sociology, becoming an important figure among so-called private scholars (Privatgelehrter). From his pen came an exceptionally valuable study of the development of Poznan20, without which it is difficult to bypass anyone who takes up the issue of the history of Poznan in the 19th century21. An amateur scientist was accorded no less respect in the late 19th and early 20th centuries than a university-trained scientist, if his knowledge and skills legitimized him. Although photography was not a science, Sallem Jaffé managed to find himself among the elite of local humanists. And this was because he used photography as a cognitive tool.

His background and place of residence, not unlike Moritz's, were of vital importance. Both were beneficiaries of the Jewish enlightenment movement - the Haskalah, which developed in Poznan only under the Prussian partition. It was education that allowed Jews to emerge from isolation, and although the Jewish community became Germanized in the process22, education deepened its members' connection to the city, its culture and history. Among other things, Sally Jaffé expressed it in donations of her own photographs to the local museum (Provinzialmuseum Posen) and historical society (Historiche Gesellschaft für die Provinz Posen23) and, above all, serving as an initiator and later as an active board member of the local photographic society Photographischer Verein zu Posen. This local patriotism expands the background of his photographic passion and mission to include work for the city and the integration of the local intelligentsia - Jewish, German and Polish. Salle Jaffé's intellectual potential from the Enlightenment movement made him a leading figure among the members of the Photographischer Verein - middle-class amateur photographers who undoubtedly all belonged to the intelligentsia at the time, but only a few had similarly creative minds.

Photography for science, or art

From the mid-19th century began the process of "colonization of image culture"24 by photography, which Adam Sobota summarized as follows: In modernizing societies, it was photography that became the standard by which realism and modernity of art were judged. Photography undermined the terrain of art and forced it to constantly change form, competing with art on every level25. Thus, in the era of Jaffé, the dual nature of photography - as a tool of the artist and at the same time his product - was clearly revealed. It was put more philosophically by Susan Sontag in her famous collection of essays About photography: a photograph is not only an image (...), an interpretation of reality, but also a trace, something reflected directly from the world26. This duality requires the photographer to have the same respect for technique as for art. This redoubled respect characterized some 19th-century artists in other fields of art (especially architecture, design), who, influenced by the Industrial Revolution, even advocated functionalism, eventually implemented much later27. When it comes to photography as a technique and art of documentation, functionalism is its original essence. And this is what fascinated Jaffé.

With the end of the nineteenth century for the alliance of technology and the art of photography in Europe, most did Alfred Lichtwark, director of the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, organizing a huge international exhibition of 6,000 photographs by nearly 500 amateurs at the art gallery in 1893. Although it is more often considered a demonstration of the appreciation of amateur art photography, Lichtwark's motivation was his belief that amateurs could refresh photography. It was they, he believed, who had the chance to free it from the retouches i rupees from the atelier28. The Hamburg gallerist did not negate the technique of professional photographers, he wanted freedom for it, to cross boundaries.

Jaffé, present at the Lichtwark exhibition with as many as 20 works - views from Switzerland, among others, in diapositive technique and indefinite stereoscopic photographs29, he clearly sought freedom of technical choices. He experimented with constantly new ways of capturing images on film (diapositive, stereoscopy) and presented himself in Hamburg precisely because not only was amateur photography allowed before the public there in the ennobling space of the Kunsthalle (Lichtwark: To the audience, it seemed as if the congress of naturalists wanted to use the church as a meeting hall30), but at the same time its arbitrariness was recognized. None of Jaffé's work won laurels, so at the time he was a representative of the possibilities of the multitude of amateurs rather than an outstanding photographer. On the other hand, three years later he received a prize in Berlin for photographic writing31, and four years later - for scientific photography, building a position based on photography as an object and tool of cognition, aware that this too falls within the realm of art. Photography, the only significant contribution of science to the arts, has its legitimacy, like all media, in the total uniqueness of its means32 - assessed American photographer Paul Strand in 1922. It was a position grounded in the attitude toward photography of decades past.

Poznanians in the vanguard of North German photography

To Sallem Jaffé as early as 1895, when he co-founded the Photographischer Verein zu Posen, just uniqueness of the measures allowed significant contribution to the arts By photographing. It's all about the adventure of repeating the experiment Wilhelm C. Röntgen at the end of 1895 and the beginning of 1896, a joint work of his and his colleagues in the Verein, bearing witness to his participation in the most current cultural phenomena of the late 19th century and his success in the supra-regional space, i.e. in northern Germany. I wrote about it more extensively in a volume on Poznan photography from 1839-1945, emphasizing the absolutely avant-garde dimension of the results of the33. The X-ray pictures taken not only aroused the admiration of the crowds of Poznans during the demonstrations at the Victoria Hotel. They were also published as illustrations of almost the entire issue of the Berlin magazine "Photographische Mitteilungen" dedicated to the discovery and the famous Röntgen treatise - because the Poznans were leading the way! The editors announced:

we believe that we are the first North German journal to submit to its readers the most important results of Röntgen's experiments. The new Poznan photographic society drew the freshest news immediately into the field of its experiments, and to this with the greatest success34.

On the part of the editors, this was a good face to a bad game, because in the next issue they had to explain why they had not published photos from the electrical engineering laboratory of Berlin's Königliche Technische Hochschule, which was subordinate to the editor-in-chief. The reason given was mundane - a sudden shortage of X-ray machines in the capital35, but the reason could just as well have been the failure to repeat Röntgen's experiment. The Poznans were even praised by the editors for choosing "Photographische Mitteilungen" as the organ of the Photographischer Verein zu Posen: We value this honor all the more because the young society has, from its earliest days, set an eminently scientific course that many societies could take as an example36. It's hard not to see this as a tribute to a success that the Berliners had not yet achieved at the time. However, I believe that Jaffé and colleagues received praise from everywhere for the X-ray photographs understood in a double sense - scientific and symbolic. After all, such photographs made a longer-lasting impression that has long been forgotten. Revealing the interior of humans (and other beings) reached the dimension of secular mysticism. Sontag fished out of Magic Mountain Thomas Mann's plot of the X-ray of the unattainable beloved of the bather Hans Castorp. For him:

The X-ray of Klawdia, which showed not her face, but the delicate bone structure of the upper half of her body and her respiratory organs, surrounded by a pale, unearthly envelope of flesh, is a most valuable trophy. "Transparent portrait" is a far more intimate trace of the beloved than the "external portrait" painted by the court counselor (...), which he once gazed upon with such great desire37.

This way of interpreting a technical X-ray illustrates perfectly the freedom that photography has gained in the modernizing societies, mentioned by Saturday. At the same time, he realizes how far the intellectual element permeates it.

With the current of Berlin scientific photography

At Jaffé and several other members of the Poznan photographic society, like a professional Joseph aka Joseph Engelmann whether writing reviews and larger dissertations Friedrich Behrens, involvement in the movement for photography must have been at least in part the result of contact with the Prof. Hermann Wilhelm Vogel - Editor-in-chief of the "Photographische Mitteilungen" cited above, founder of the first Berlin photographic societies38. Engelmann may have encountered him since at least 189539, Behrens - since January 3, 189640., Jaffé since 189441. or earlier.

Photochemist Hermann W. Vogel (1834-1898), a unique figure in the Berlin milieu, posed challenges and met them himself. Along with several other scientists, he made the German capital a center for the development of photography for the natural sciences, so as a cognitive tool, and also led to an organized amateur movement. In 1863, alongside the first society of photographers in Germany, he established a photographic laboratory at the institute of crafts (Königliche Gewerbeinstitut), where a year later he led Germany's first chair of photochemistry. From 1879, he held the same position at the newly established technical university42 (The laboratory there "lost" the race to repeat the Röntgen experiment with the Poznans). He published a textbook on photography43 and wrote on techniques, and participated in American photographic events, including as a juror for photography, lithography and oleo-printing at the 1876 World Exposition in Philadelphia.44. Not coincidentally, in 1883, Vogel's pupil became a Alfred Stieglitz, later a reformer of the American photographic scene, but already active as a student in Berlin. It was he who, in 1887, called for the creation of an all-German amateur organization. Vogel immediately responded and established the Deutsche Gesellschaft von Freunden der Photographie45. And in 1896 he counted 35,000 amateurs in Germany46, still few for Germany, but among them were already cognizant.

Photography in Berlin had to be used for something: the proper representation of Berlin is seen not in the field of art photography, but in scientific photography, because, after all, these are professional works47 - ironized a correspondent bitterly in the same 1896, complaining about judging the work of amateurs in terms of flimsiness. The implication, however, is that by combining art with science and documentary, the photographers affiliated with the Verein zu Posen initially followed the path of the Berliners and immediately fit into one of the two main currents of German photography, over time reaching the other - Hamburg's, testing earlier and more intensely artistic pictorialism. This can be seen brilliantly in the work of Salle Jaffé48. But first a digression: Berlin was the cradle of the Haskalah, and Stieglitz's parents had the enlightenment attitude characteristic of its beneficiaries49. It is worth tracing the extent to which one and the other influenced the photographic path of Jaffé and Alfred Stieglitz (why Berlin?), how long the ferment that the latter sowed in Berlin circles in 1887 had resonance among Jewish artists and academics, how much was said about him. Jaffé was already taking pictures in the mid 1880s, and could have known Stieglitz by then - at least since 1872 his sister Clara Mühsam had lived in Berlin, and since 1874 the other, Regina Portner50. The contact may have come through Vogel; was Jaffé, for example, even among the free listeners of this professor? Also giving food for thought is the fact that Stieglitz had in his book collection the works of Behrens51. Relationships with a famous American would raise the profile of the cognoscenti more than Berlin connections.

In Berlin of Wilhelm II's time, just as in Poznan, old buildings were demolished to create a city from scratch. Jaffé earlier than Eugène Atget In Paris after the great reconstruction perpetuated the remains of the old city52. At the same time, he was taking pictures along the lines of the Berliners, whose photography of the city not only reflected the existence of history in its historical evidence, but also succumbed to the projection of national history, used to demonstrate and bolster future goals53, as put by Miriam Paeslack, author of the comprehensive study Fotografie Berlin 1871-1914. In the 1890s, he took a number of interesting photos that fill the hallmarks of historical documents - of the shelter, the renovation of the Old Town building and the demolition of the Catherine Convent . Jaffé was inspired by the same particular fascination with the theme of demolition54, which some photographers of the German capital, trying to capture at least on film remnant of the good old days55. Such was Jaffé's motivation, along with other members of the city's intellectual elite, especially the one established in 1885. Historische Gesellschaft für Provinz Posen. The photographs of Jaffé mentioned above come from the collection of this particular association.

Before 1900, he also photographed views of places that had previously changed or were about to change, for now gently hinting at "national history" with a suggestion of "future destinations": the bread sheds under the Scales, New Street with the tramway, the courtyard of the old commandery, and the busy end of Wilhelm Square in front of the old Provincial Museum building. They are a valuable picture of the city together and separately. Although the photos, mostly also from the collections of the Historische Gesellschaft, were clearly commissioned, the author consciously created the collection. This is an influence from Hamburg, where entrepreneur and patron of photography Ernst Juhl spent years collecting works by amateurs with views from the city (he had Jaffé's work)56, first privately, and over time on the order of the magistrate. In Berlin, such a commission did not occur until after 1910, although, significantly, there were already collections documenting the city in the 1880s57. Nevertheless, the subject matter and composition of the architectural photos share the same characteristics as the work of metropolitan Berlin photographers - Jaffé preferred a perspective view to a frontal one58, which, as Vogel wrote in an 1870 textbook. - is in full compliance with the rules of the art59, and was widely used by Berlin photographers of the lat. 1890s. Attention is especially drawn to the view of the old Provincial Museum building with people scattered on the square - it captures the movement, the disorder, the pace of a big city. Life.

Many more historical photographs of the city were made between 1900 and 1913. Landscapes embedded in the pictorial trend are a marginal, though time-consuming, part of Jaffé's oeuvre60. Working on them made him an expert in noble techniques, so it was a further intellectual adventure that had new cognitive qualities, required hundreds of trials and errors, and which he disseminated in the form of prints and by publishing the conclusions he drew. The rich, intelligent, educated trader sought self-realization in an area contrasting with his particular profession. At the same time, he stood firmly on the ground (after all, landscapes with views of nature are also a document). Jaffé's life's work remains his photographs of the city - some 80% of his well-known oeuvre, in the new century often very warm in expression thanks to bold frames with a lowered perspective, which are filled with air, light and vividly passing people on the streets. They present the spirit of the times and the emerging photography of the new metropolitan everyday life, which was captured to be known, to be ordered, to be preserved. Jaffé, aware of the importance of historical documentation, donated a sizable collection not only to the Historische Gesellschaft, but also to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum61, a plethora of illustrations provided for a major study of Poznan in 1911 by a fellow intellectual - the esteemed amateur historian Arthur Kronthal62, also a Jew. He worked for posterity. Jaffé's photos published by Kronthal - views of the buildings and panoramas of the modernized city built in a few years before their eyes - are already a definite example of projection national history, used to demonstrate and bolster future goals, with the proviso that the peculiarities of the Poznań concept national history she put a question mark around it. National, meaning German? Rather, it is a projection of the emergence of a modern city and modernly served, close in style to the photographs of Berlin whose production in the early 20th century satisfied the needs of the editors of exquisite illustrated magazines and the mass market of postcards or albums. Above all, however, Jaffé's works show how close he was to Poznań. There is no other such collection of photographs documenting local development. This local patriotism was shared by the Jewish photographer mainly with Polish intellectuals; a strong turnover prevailed among Germans from the 2nd half of the 19th century onward, and after a few years they usually returned to the depths of Germany, without identifying themselves with the city. Despite all of Jaffé's ties to German visual culture, to understand his work in Poznan under Prussian rule, it is necessary to articulate the complex context of this particular intellectual practice, realized through photography, documenting reality with fidelity to a technique specific only to this medium.

Footnotes:

S. Sontag, On Photography, New York 1977; first ed. pol: About photography (translated by Slaw Magala), Warsaw 1986. Sontag's essays first appeared in the New York Review of Books (1973-1977). ︎

Cf. M. Boguni-Borowska, P. Sztompka, Photosociety. An anthology of texts in sociology (Krakow 2012). ︎

Exhibition Poznan photographer Sally Jaffé, November 7, 2021 - January 30, 2022, curated by Ewa Hornowska. ︎

The photos appeared in the catalog concluding S. Jaffé's monograph: E. Hornowska, Poznan photographer Sally Jaffé, Poznań 2022 [hereinafter: Hornowska 2022], pp. 201-302. ︎

M. Warkoczewska already in the 1960s attributed and described S. Jaffé's photographs in the Museum of the City of Poznan, which stores the documentary part of the photographer's oeuvre (she inventoried them; some were published, and she also wrote about Jaffé in, among other places: Poznan in an old photograph, Poznań 1967, Poznan yesterday. Posen gestern, Poznań 1998). E. Stęszewska-Leszczyńska in the late 1980s and early 1990s discovered and processed photographs of synagogues in the collection of the UAM University Library [hereafter BU] (published in the text of the Poznan synagogues, "Chronicle of the City of Poznań" 1992/1-2, pp. 102-118). ︎

I give the approximate number of photos in the MNP's holdings after the exhibition's curator E. Hornowska. ︎

I got the information about the number of photos at BU from Jakub Skutecki, curator of the collections of BU's Iconographic Studio. ︎

The photographs of S. Jaffé in the collection of the Municipal Conservator of Monuments in Poznan are not signed, so it would be necessary to identify them on the basis of comparative research. ︎

Cf. Hornowska 2022, item cat. I/3. ︎

Jw, p. 84. ︎

Ibid, p. 88. ︎

Jaffé's exhibition also had a trailer in the form of a podcast, albeit an exceptionally short one; cf. https://youtu.be/UXbcWJ6Bbnk ︎- Cf: S. Sontag, The sight of someone else's suffering, Krakow 2010, p. 142. The author mentions an advertisement for clothing manufacturer Benetton - a photo of a Croatian soldier's bloody shirt during the war in Yugoslavia. This is an example of weakening the direct message from any war. ︎

The Family of Man is on permanent display at Clervaux Castle (Luxembourg). ︎

Cf. photos from the exhibition [at]: https://fixthephoto.com/best-photography-museum.html; https://www.icp.org/exhibitions/weegee-murder-is-my-business; https://www.kunstleben-berlin.de/germaine-krull-fotografien-im-martin-gropius-bau/; https://www.magnumphotos.com/theory-and-practice/understanding-the-fine-art-market-three-fundamentals/ [accessed 1.04.2022]. ︎

Cf. https://www.krakow.pl/aktualnosci/209805,33,komunikat,portret_-_nowa_wystawa_stala_w_muzeum_historii_fotografii.html [accessed 1.04.2022]. ︎

https://mnp.art.pl/wydarzenia_i_wystawy/ black-on-white-in-color/ ︎

Quoted [after] W. Kemp, History of Photography. From Daguerre to Gursky (translated by M. Bryl), Cracow 1998, p. 53. ︎

Reproduced [in:] M. Piotrowska, Alternative Lives. Amateurs and professionals in Poznan photography from 1839 to 1945, Poznan 2019, p 126. ︎

M. Jaffé, Die Stadt unter preussischer Herrschaft, Posen 1909; pol. ed: Poznan under Prussian rule, edited by P. Matusik, Poznań 2012. ︎

P. Matusik, Introduction [in] M. Jaffé, ibid, p. 5. ︎

Anti-Semitism was also fueled by the prominent material position of the Jews; more about their situation in Poznan in the 19th century, among others: L. Trzeciakowski, Social and political changes among the Jews of Poznań in the early 19th century, w: Germans and Jews in Poznan, "Chronicle of the City of Poznań",1 1992/1-2, pp. 79-80; R. Witkowski, The road to Germanness? Jews in the Grand Duchy of Poznan, (w:) Poznan's way to independence, edited by A. Gulczynski, Sz. Paciorkowski, Poznan 2021, pp. 248-249. ︎

Cf. E. Hornowska, Poznan photographer Sally Jaffé, Poznan 2022 (hereafter: Hornowska 2022), pp. 39-41. ︎

Steve Edwards' term in: Photography. A very brief introduction, Krakow 2014, p. 24. ︎

A. Saturday, The Nobility of Technique. The artistic dilemmas of photography in the 19th and 20th centuries., Wroclaw 2001, p. 40. ︎

S. Sontag, About photography (translated by Slaw Magala), Warsaw 1986, p. 162. ︎

In the context of photography, he pointed out that. A. Saturday, Nobility…, OJ, p. 17. ︎

Terms from a statement by Alfred Lichtwark (translated by MP), quoted [after:]. Chronik 1908-1998. DVF (Deutscher Verband fűr Fotografie e.V.), Chronik_neu_11-2005, pdf, p. 8/9. ︎

Cf. Hornowska 2022, pp. 93, 160. The works mentioned are known only from a mention in the catalog. ︎

Quoted [after] W. Kemp, History..., OJ, p 42. ︎

For photographic writing, S. Jaffé was awarded at the International Exhibition of Amateur Photography., for scientific photography - at Anonymous exhibition; information on participation in exhibitions [for:] Hornowska 2022, pp. 93-94. ︎

Quoted [after] W. Kemp, History..., cited above, p. 54. ︎

Cf. M. Piotrowska, Alternative Life...., op. cit. pp. 28-32. ︎

Jw., p. 31 (translated by MP). ︎

See ibid, p. 32. ︎

Jw., p. 33. ︎

Quoted [after] S. Sontag, About photography, cited, pp. 172-173 First edition Magic mountainsy was published in 1924. ︎

In 1863, on Vogel's initiative, the Photographischer Verein zu Berlin was founded as the first photographic association in Germany, renamed Deutscher Photographen-Verein in 1867; in 1869, the Verein zur Förderung der (Amateur-)Photographie, led by Vogel, emerged from there, publishing "Photographische Mitteilungen" (hereinafter: "Phot. Mitt.") and nurturing scientific interest in photography; from this, Vogel again formed in 1887 a nationwide organization for amateurs, the Deutsche Gesellschaft von Freunden der Photographie (from which the Freie Photographische Vereinigung, to which Jaffé had belonged since 1894, was spun off in 1889). ︎

Engelmann was a member of the Deutscher Photographen-Verein at least in 1897 (Hornowska 2022, p. 55), already in 1896 it was written that he was a long-time member of the Verein zur Förderung der (Amateur-)Photographie ("Phot. Mitt" 1896, Jg.32, H. 21, S. 353 stated: "unserer langjähriger Mitglied"/our long-time member), and in 1895 he published a photograph in "Phot. Mitt." (H. 1, April [I]); M. Piotrowska, Alternative Life...., op. cit. pp. 34, 35. ︎

Behrens made a guest appearance at the Verein zur Förderung der Photographie on January 3, 1896, and was praised by Vogel (M. Piotrowska, Alternative Life..., cited, p. 32). ︎

Since 1894, Jaffé had been a member of the Freie Photographische Vereinigung zu Berlin (Hornowska 2022, p. 159), which was not headed by Vogel, but the cognoscenti were able to seek contact through it with the man who was to publish the X-rays co-authored by Jaffé two years later - that man was Vogel. ︎

On H.W. Voglu [for:] M. Paeslack, Fotografie Berlin 1871 - 1914. Eine Untersuchung zum Darstellungswandel, den Medieneigenschaften, den Akteuren und Rezipienten von Stadtfotografie im Prozeß der Großstadtbildung, WS 2001 (dissertation at the University of Freiburg), pp. 104, 310-311, 314-315; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Miriam-Paeslack/publication/29758578_Fotografie_Berlin_1871-1914_eine_Untersuchung_zum_Darstellungswandel_den_Medieneigenschaften_den_Akteuren_und_Rezipienten_von_Stadtfotografie_im_Prozess_der_Grosstadtbildung/links/587fbc6208ae9275d4ee38e0/Fotografie-Berlin-1871-1914-eine-Untersuchung-zum-Darstellungswandel-den-Medieneigenschaften-den-Akteuren-und-Rezipienten-von-Stadtfotografie-im-Prozess-der-Grosstadtbildung.pdf [accessed 2.04.2022]. ︎

H. Vogel, Lehrbuch der Photographie. Theorie, Praxis und Kunst der Photographie., Berlin 1870. ︎

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Wilhelm_Vogel [accessed 1.04.2022]. ︎

M. Paeslack, Photographs..., OJ, p. 314 (with footnote 678). ︎

Jw., p. 310. ︎

M. Allihn in "Photographische Correspondenz"; quoted [after] M. Paeslack, ibid, p. 105 (translated by MP). ︎

I omit here, for lack of space, the marginal theme of Jaffé's membership in the Vienna Society. ︎

At least the Stieglitz sons were educated, one became a chemist (Julius, studied in Berlin), the other a medic; the mother's cousin was a professor at City College in New York; https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Stieglitz [accessed 1.04.2022]. ︎

Por. https://www.geni.com/people/Regina-Portner/6000000022552233379; E. Hornowska writes (dz. cit. pp. 24, 55) that Jaffé's third sister Selma also lived in Berlin, which, with a cursory search, cannot be confirmed before her divorce from Arnold Sternfeld, and that she had previously lived in Munich, cf. https://www.stolpersteine-berlin.de/en/biografie/3200, https://www.geni.com/people/Selma-Sternfeld/6000000022552581987) [accessed 2.04.2022]. ︎

Cf. M. Piotrowska, Alternative Life..., cited above, p. 38. ︎

Cf. reproductions before 1891 in: Hornowska 2022, catalog, nos. I/9, I/10, I/22. ︎

M. Paeslack, PHOTOS..., cit. p. 116 (translated by MP). ︎

Jw., p. 137 (translated by MP). ︎

Quoted from the illustrated magazine Berliner Leben, [after] M. Paeslack, ibid (translated by MP). ︎

Juhl acquired a heliogravure Street by the canal; see Hornowska 2022, pp. 110 and 268, cat. no. II/23. ︎

A collection of documentary photography was held by the Märkisches Museum in Berlin; Ernst Juhl's collection in 1910 included about 400 photographs; M. Paeslack, Photographs..., cited above, pp. 104, 108-109. ︎

Cf. M. Paeslack, Photographs..., cited, p. 133 and reprod. nos. 39-45. ︎

Quoted [after] M. Paeslack, ibid, p. 133 (translated by MP). ︎

There are less than 25 such landscapes out of 115 known photographs (originals or reproductions) (cf. Hornowska 2022, Catalog). ︎

He donated the photos in 1913, when he moved to Berlin (cf. Hornowska 2022, pp. 188-189). The Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum was the successor to the Provinzialmuseum (Provincial Museum). ︎

A. Kronthal, Die Residenzstadt Posen und ihre Verwaltung im Jahre 1911, Posen 1911. Kronthal was a factory owner, councilman, member of the magistrate, and community activist. ︎